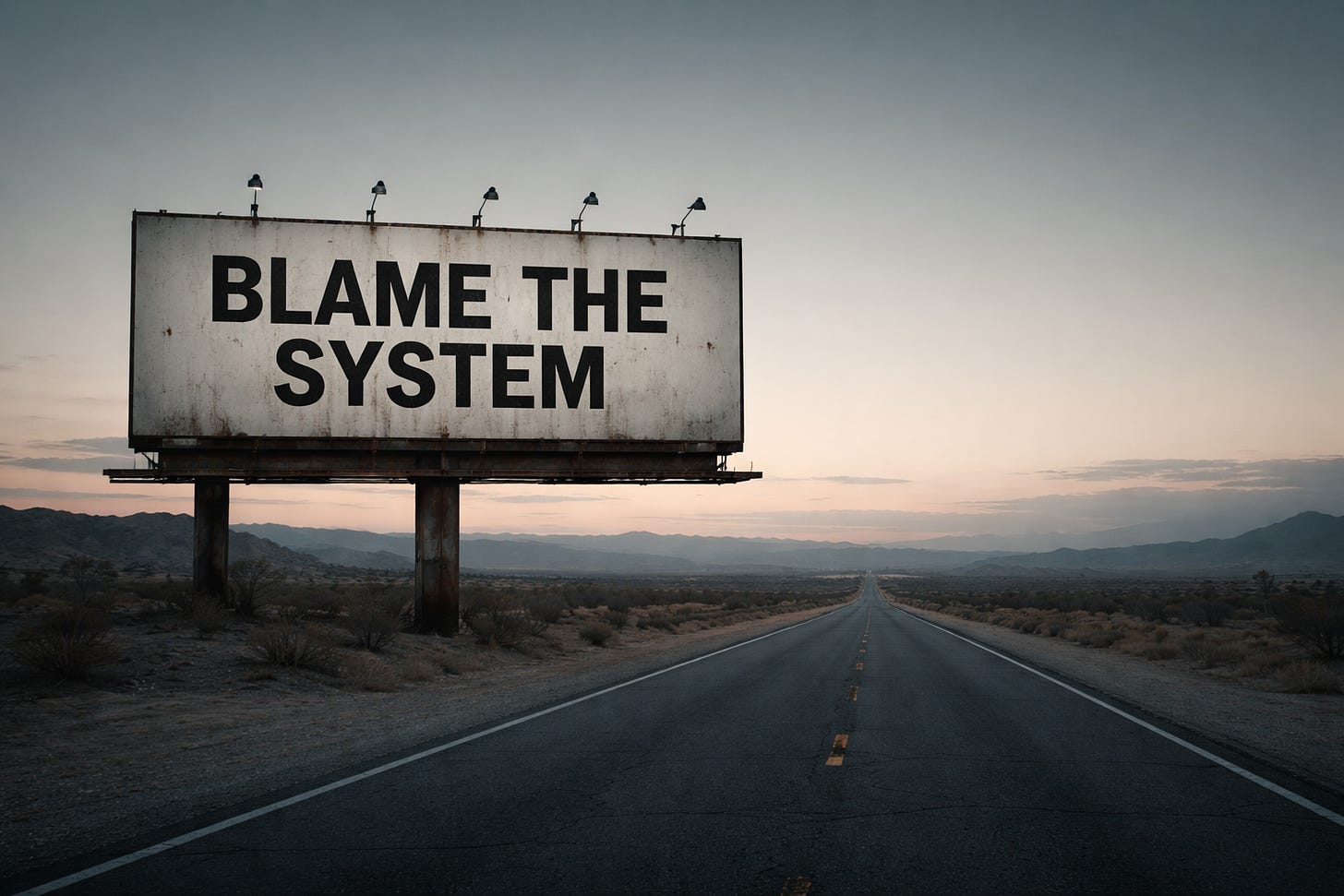

Blame the system

When the human factor is inconvenient

I used to be someone who could deliver a passionate rant monologue about the big bad system. I believed we’d all be better off, especially women, if it were redesigned to serve us.

My view changed after years inside systems enforced by professional managerial class (PMC) women. What I experienced was assimilation rather than liberation, despite the promise of feminism. Over time, it became harder to ignore that the system was only one part of a much messier set of conditions shaping who benefits, who advances, and who gets pushed out through scapegoating.

As a result, I’ve become increasingly sceptical of how quickly the system is blamed when people don’t get the outcomes they want.

I’m not denying that systems are important. They absolutely are. Systems shape incentives and enforceable limits on behaviour. They distribute opportunity and protect certain outcomes over others. They aren’t neutral, but they’re also not divine, omnipotent, or self-correcting. They’re manmade, built to enable coordination or flourishing under particular assumptions about how people will act.

Most systems function exactly as designed because those assumptions are rarely examined once the system is in motion. These assumptions are that people will act in good faith, share broadly similar moral norms, and regulate themselves without constant enforcement. In other words, many systems presume moral homogeneity, self-restraint, and personal responsibility, while neglecting the unconscious emotional drivers that shape action and decision-making.

When those assumptions are shown to be false because norms fragment, feedback loops weaken, and accountability diffuses, even well-intentioned systems destabilise. What looks like corruption is often a combination of bad faith and the system revealing its own assumptions. In that sense, systemic failure reflects misconduct, lack of accountability, and design premises that no longer constrain behaviour as intended.

This is part of my thinking about how quickly blaming the system becomes a stopping point rather than a starting question. In some cases, it functions less as analysis and more as a way of deflecting responsibility away from the behaviour of the people inside it. Blaming the system can offer certainty and moral clarity, but it also risks simplifying the more uncomfortable interplay between structure and behaviour into something easier to understand, but not necessarily accurate.

Responsibility is harder to pin down if the system is always to blame.

When outcomes are described as systemic, it becomes unclear who acted, who had options, who chose not to restrain themselves, or where repeated behaviour should be examined. Responsibility diffuses.

This is why I’m offering the definitions below as a form of inoculation. They reflect how I try to think: interrupting the pull toward black-and-white explanations, noticing when situations slide into the Karpman Drama Triad, and returning attention to agency and individual responsibility without pretending systems don’t matter.

They’re meant to counter language that explains repeated bad behaviour without naming the people involved. Systems, cultures, structures, and ideologies are blamed, while the individuals who act, repeatedly, are described as invisible, faultless, or powerless.

The point of these definitions isn’t to deny context or conditioning. Behaviour is shaped by different forces such as incentives, pressure, and what’s at stake in any situation. My point is to keep human agency and personal responsibility at the forefront when systems are discussed.

These definitions apply to patterns of repeated behaviour, not one-off incidents. I’m bothering to propose some clarity because we’re living in a time when moral language signals moral behaviour, substituting for behaviour constraint.

Part of what complicates these conversations is how moral language now operates in public and institutional settings. By moral language, I don’t mean ethics in a philosophical sense, or ordinary judgments about right and wrong. I mean language that frames situations primarily in terms of moral standing rather than behaviour: who’s good or bad, harmed or protected, righteous (and at times, the oppressed) or oppressive.

Moral language pulls attention away from behaviour and makes it harder to see how outcomes are actually produced.

Some systems do real damage when the same people in the same roles keep responding in the same ways despite having humane alternatives, and no one stops them.

Individual responsibility

Systems influence behaviour, but individuals enact injury. In interpersonal contexts, responsibility remains with the person who repeatedly chose, continued to choose, or failed to restrain behaviour that causes material, relational, or psychological injury to another over time or across repeated interactions.

This definition applies to:

repeated acts against the same person

the same injurious behaviour enacted across multiple people

situations where there were multiple opportunities for restraint or correction

It doesn’t apply to isolated incidents, emergencies, or singular high pressure events involving forced decisions under severe time constraint.

Group responsibility

Systems influence collective behaviour, but groups generate injury through repeated, coordinated, tolerated, or unrestrained patterns of action. Responsibility therefore lies with those who initiate, enable, legitimise, or fail to constrain behaviours that cause material, relational, or psychological injury across time or across multiple people.

At the group level, responsibility is role-based, not collective guilt. It belongs to those with influence, authority, legitimacy, or a duty to restrain, not to membership alone.

When structure becomes the explanation

These definitions keep coming up for me when I look at contemporary debates about inequality, where the system is treated as the cause rather than as the context in which people act.

Structural analysis can be useful. It can show constraints, incentives, and history but it often stops there. In debates about gender inequality, pay gaps, or leadership representation, disparities are frequently taken as proof of systemic wrongdoing on their own, while the behaviours, strategies, decisions, and trade-offs that sustain those patterns are left largely untouched.

This framing becomes especially compelling when people hold authority but can’t influence outcomes. Authority without influence produces frustration and a sense of powerlessness. Structural explanations offer a way to name that frustration without having to account for how influence is actually granted, withheld, or lost.

My overall issue is that structure increasingly functions as the endpoint of explanation. Explaining outcomes this way makes responsibility unassignable. Attention shifts away from human action and systems are treated as sufficient causes in situations that would otherwise require examining who acted, who benefited, who complied, and who repeatedly chose not to intervene. I understand the appeal of certainty in situations marked by harm and conflict, but narratives that externalise responsibility tend to entrench grievance and entitlement rather than interrupt the behaviour producing the harm.

That framing can be satisfying but I’m not convinced it helps much if the goal is to understand why outcomes persist or how they might actually change.

I’m sharing this because I’m finding it harder to think clearly when everything is explained away as systemic and no one is responsible for anything anymore. If you see this differently, or have a better way of making sense of responsibility and systems, I’m genuinely interested in hearing it.

Thanks for reading,

Nathalie

Hack Narcissism and support my work

Hacking Narcissism is for people trying to make sense of and effectively navigate a morally distorting and chaotic age. When moral development is disincentivised, people lose reliable reference points for discernment and struggle to distinguish between what’s real, what’s performative, and what’s covertly shaping their perception.

Narcissistic traits are expressed in everyone (often referred to as Cluster B traits). They flourish during periods of moral decline because they help secure status, protection, and significance in environments where norms of what appears correct, rather than what is grounded in moral principles, regulate behaviour. The effect of this behaviour is experienced in all types of relationships, including in workplaces, where people can be punished for violating norms they never agreed to and were never made explicit.

By supporting my research and writing, you’re supporting an effort to understand the processes shaping reality and relationships, to disentangle from dysfunctional relational dynamics, and to remain anchored to truths that guide perception rather than allowing external influences to shape it. Your support enables me to continue making sense of patterns that many people recognise but struggle to articulate, and to clarify the actions that allow people to free themselves from those patterns.

Here’s how you can help:

Order my books: The Little Book of Assertiveness: Speak up with confidence and The Scapegoating Playbook at Work

Support my work:

through a Substack subscription

by sharing my work with your loved ones and networks

by citing my work in your presentations and posts

by inviting me to speak, deliver training or consult for your organisation

With respect to the Post Office scandal, the Horizon inquiry Lord Arbuthnot who was Jo Hamiltons MP said on talk TV in 2023, this has gone beyond being a computer problem (systems problem) this has become a human problem. In 2014 when I realised that technical hard work and growth was not cutting it I realised that my future lay in human centricity, feedback, agility through continuous improvement, unconscious habitudes and plastic brains. Thank you for supplying me with a continued flow of essential self aware posts and articles. 🙏🙏

I agree. Individual responsibility will always be necessary as a central part of relationships, because we live the systems in relationships and common places, not in a vacuum.

On the other hand, systems approach is used because it makes sense (particularly if it's used with prudence): if systems influence and structure the lives of millions of people, then we can look at a system and see behaviours and repeated problems that typically emerge within that system. Then, if we want different "wide" outcomes, we can try a different system to prevent having the outcomes we don't want anymore.

A good example is that criminality arises where socioeconomic inequality is high (as in countries like Haiti, or El Salvador some years ago), while criminality is low in prosperous countries. Not only in countries, but also in the cities and neighbourhoods that fill those descriptions within a same country. This suggests that socioeconomic inequality (more on the side of poverty than wealth as crime is concentrated in poor areas, but also in wealth to an extent) correlates to risk factors for criminality: high stress, family dysfunction, lack of education, mental health problems, etc.

It doesn't make criminality less horrible, but it makes the wide context understandable in order to prevent future generations of criminals: the most peaceful countries are the most prosperous AND less inequal (this difference is relevant), and I believe they have other factors in common as well: they tend to be geographically small and neutral in wars (in practice, and even officially like Switzerland), etc.