When praise turns into attack

Covert control tactics continued

I had intended to finish part two of my series on envy by now, but my attention had been drawn elsewhere until something suddenly brought me back to the topic. Cluster B behaviour attacks have a way of snapping my focus to where it needs to be. Rather than speak directly about envy here, as that will be explored in the forthcoming article, I want to look more closely at the hidden motives that shape how people behave online, and at times, offline.

Sometimes the trigger doesn’t appear immediately and emerges when my work begins to stretch beyond someone’s comfort zone, when it no longer affirms their preferred narrative. For example, someone will reach out privately to tell me how deeply my work resonates with them, expressing gratitude and wanting either the sense of connection that comes from parasocial closeness or proximity to work they perceive as credible, sometimes even asking for an endorsement of their own projects. What they connect with, however, is not the whole of my work but a version of it that fits neatly within their existing worldview.

That balance shifts when I post something that disrupts a carefully held worldview. In this case, it was expanding the conversation beyond the totalising frame that narcissists are the sole cause of workplace abuse and suggesting instead that workplace toxicity cannot be reduced to a single personality type. When the framing no longer aligns with what feels safe or familiar, the admiration that once appeared in private begins to change. What was once expressed as resonance and appreciation becomes a public attempt to correct or discredit.

I wrote a post intended to prompt reflection rather than assign blame, asking readers to consider how scapegoating does not only happen to us but also through us; that envy is not confined to narcissists or Mean Girls but lives in all of us, especially in systems that reward compliance over competence. The majority of the reception were public resonance, and private messages of gratitude for the insight they now have and its healing effect.

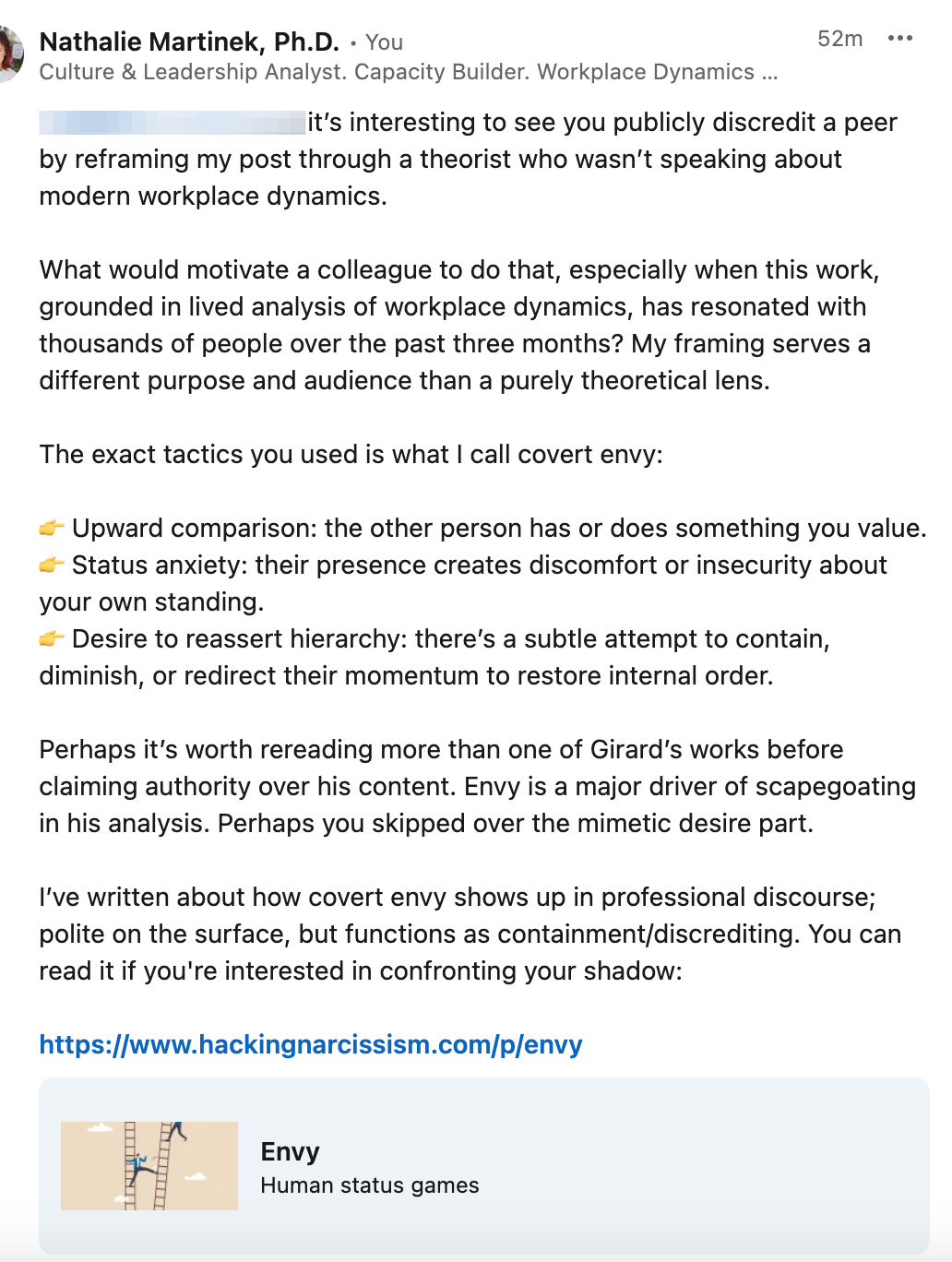

Then someone reshared it with this reframing:

Actually, according to the late social theorist René Girard, who dug more deeply into the phenomenon known as scapegoating than anyone who ever lived, envy has nothing to do with a group's felt need to scapegoat an individual. Rather, it has everything to do with the group's felt need to absolve itself of all moral responsibility and the shame that the members of the group would feel if not for the relief provided by the human sacrifice.

Source: The Scapegoat by René Girard (1977).

This is a clear example of what I described as covert expressions of envy. The post appears collegial, even helpful, yet its underlying function is to discredit and diminish, following a very predictable pattern.

First, there is the upward comparison. My work had a reach and accessibility that created an uncomfortable tension. It resonated in a way that quietly unsettled their own standing.

Next is status anxiety. A framing drawn from a detached analysis of personal experience can connect more widely and immediately than niche theoretical discourse. That accessibility can feel destabilising to those whose authority rests on specialised knowledge.

Finally, there is the desire to reassert hierarchy. To neutralise the discomfort, an external authority, in this case, Girard, is invoked as the sole legitimate voice on scapegoating. By positioning him as the only true expert, and by extension framing his theory as the only acceptable lens, my work is implicitly cast as fraudulent or derivative even though Girard never wrote about scapegoating in the context of modern workplaces. It is a subtle but effective way to make undiscerning readers distance themselves from my posts without questioning why. On the surface, it looks like collegial feedback. In reality, it narrows the conversation, redirects attention, and restores the hierarchy to its familiar order.

I value disagreement offered in good faith because it can bring depth and nuance to a conversation, but that was not what happened here. The difference in perspective was presented as an authoritative correction, a subtle discrediting, and a shutting down of other ideas rather than a genuine attempt to expand the dialogue.

I couldn’t resist adding my thoughts in response to this person who had once spoken effusively about the importance of my work. As I drafted my reply, I became curious about who had liked his post. What I noticed was revealing: several people who had recently reached out to me privately sharing how much my posts had resonated with them, how they had helped them see what was happening, and even inquiring about working with me to support their recovery, were now visibly aligning themselves with his reframing, liking and commenting on the post.

This is how the shift happens. A polite correction cloaked in intellectual authority appears, positioning itself as the deeper and truer perspective. It narrows the conversation by policing language, citing rigid definitions, and claiming ownership over what is proper to say. It returns the discussion to a fixed frame because any complication of the narrative threatens the sense of order and control that the simpler version provides.

This reaction is rarely contained to the individual; it ripples outward as the group responds in predictable ways. People who once expressed private support and validation quietly align themselves with the correction, lending it weight through likes and subtle affirmations. Their agreement is not the result of careful discernment or a genuine shift in understanding. Rather, it serves to restore the comfort of a familiar narrative that allows them to maintain the sacredness of their victimhood, rather than face the less comfortable and less acceptable possibility of being an unconscious co‑creator of their experiences. By reinforcing the safer and more recognisable version of events, they preserve social cohesion and their moral sense of goodness through adherence to the correct narrative.

This is what Jeremy described in one of his recent pieces. Denial emerges because to see the truth would require a reckoning they are not ready for, and not because they’re incapable of seeing the truth. Denial begins as a refuge, a way to avoid the pain of confronting what cannot yet be faced. Over time, that refuge hardens into a prison, locking people into a version of reality that feels safer but is ultimately limiting.

To fully see what is happening would mean acknowledging that workplace toxicity is not as simple as blaming one type of person but a complex web of dynamics: envy, hierarchy, collective collusion. It would mean admitting that they themselves might have played a role. When that’s too much for many to confront, denial steps in to anaesthetise the discomfort. It smooths over the tension of knowing better, making it easier to belong than to discern.

Denial operates on both an individual and collective level. It’s how groups maintain stability while avoiding the rupture that would come with truly seeing what they are enabling. However, the only way to step outside of collective denial is through discernment; a quality that does not come from intelligence alone but from the willingness to tolerate ambiguity, accept complexity, and to resist the reflex to outsource judgment to the crowd as your authority.

Discernment is often less appealing than belonging. Belonging is immediate and familiar, offering safety in the crowd, while discernment can be isolating because it requires being guided by an inner authority. In hierarchical systems, belonging often means aligning with whichever voice appears safest to follow, even when it contradicts what someone already knows to be true.

You might be wondering why I’m having a kvetch about online strangers who have little significance to my life. I am describing this to draw attention to the pattern beneath such responses, to the way they work to restore control and stability when a narrative begins to feel threatened.

This is a familiar control tactic that sits at the heart of interpersonal narcissism. It is rooted in shame and, in this case, coupled with envy and a sprinkle of resentment. Together, these emotions create an internal pressure that seeks relief through control. When a preferred sense of status or identity is disrupted, the discomfort becomes difficult to tolerate, and the quickest way to restore equilibrium is to silence or discredit whatever feels destabilising or threatening to the worldview they are invested in. The response appears rational or authoritative on the surface, with an underlying need to re‑establish safety by reasserting control.

When that happens publicly, the individual response ripples outward. Others who feel the same unease but can’t put their finger on it align with the correction. They echo or like it, unconsciously reinforcing the hierarchy that feels safer to them. It is not always intentional and is often unconscious, yet it preserves the comfort of a fixed narrative and the illusion of moral certainty with it.

I write about this because it is easy to recognise these patterns out there in others, yet far harder to notice them in ourselves. The impulse to regain control when something feels destabilising is deeply human, as is the desire to belong. But when we can begin to see how shame, envy, and resentment quietly drive those moments, we create the chance to pause before repeating the same pattern.

After all, this is what Hacking Narcissism is all about.

Hack narcissism and support my work

I believe that a common threat to our individual and collective thriving is an addiction to power and control. This addiction fuels and is fuelled by greed - the desire to accumulate and control resources in social, information (and attention), economic, ecological, geographical and political systems.

While activists focus on fighting macro issues, I believe that activism also needs to focus on the micro issues - the narcissistic traits that pollute relationships between you and I, and between each other, without contributing to existing injustice. It’s not as exciting as fighting the Big Baddies yet hacking, resisting and overriding our tendencies to control others that also manifest as our macro issues is my full-time job.

I’m dedicated to helping people understand all the ways narcissistic traits infiltrate and taint our interpersonal, professional, organisational and political relationships, and provide strategies for narcissism hackers to fight back and find peace.

Here’s how you can help.

Order my book: The Little Book of Assertiveness: Speak up with confidence

Support my work:

through a Substack subscription

by sharing my work with your loved ones and networks

by citing my work in your presentations and posts

by inviting me to speak, deliver training or consult for your organisation

This is a fascinating deep dive into modern online communication dynamics.

I think one of the big issues is that NO ONE WANTS TO ADMIT THAT THEY SCAPEGOAT, FEEL ENVY, MANIPULATE, OR ENGAGE IN NARCISSISTIC ABUSE. If we’re being honest with ourselves we ALL do these things from time to time.

The people rushing to place emergent social behaviors (like scapegoating) into a neat little box are precisely the people who should be looking carefully at themselves. If you think that you’re chill, honest, never abusive or dramatic or passive aggressive - then you might be the problem!

I communicate with young women every day who make sweeping claims about themselves: “I hate drama”; “I keep it real”; “I just want you to be honest with me”. Would it surprise you to learn that these rarely turn out to be completely accurate? When people have a mental image of themselves it becomes almost impossible for them to self-correct; instead, they discredit or attack or undermine the person who’s calling their self-image into question.

Back to the original point: do YOU do this, ever? A better question is, when have you done this? Doing these things doesn’t make you bad or a ‘narcissist.’ They make you human. The badness comes in when you refuse to examine the darker elements of your personality and social behavior.

Brilliant as always. You have a way of taking apart your core narrative and then put it back together in a way that is relatable, easily digested and profound. I keep running into these issues as I am sure the rest of us do. Some people take language that isn’t “friendly” in their minds as if it’s an attack or somehow minimizing them and their identity. It’s a jungle out there…