How to spot when activism is being done to you by your helping professional

How misguided empathy fuels narcissism in helping professionals

Welcome to my new subscribers! You’ve helped me crossover into 5000 subscribers - thank you! Many of you have discovered this Substack, thanks to generous recommendations, paid subscriber endorsements, and the Notes platform. I hope you stick around and get a sense of how I dissect interpersonal dysfunction, also known as interpersonal narcissism, in so many different contexts. If you want to get started on learning about this Substack, check out this compilation.

In this premium piece, helping professionals refer to medical professionals, therapists, counsellors, pastoral and spiritual carers, lawyers, coaches, psychologists, clergy, naturopaths, spiritual healers, psychedelic facilitators, bodyworkers, and allied health professionals. The emphasis is on what activism looks like in practice, why it’s problematic, how to spot it if you’re the client or the helping professional, and what to do instead.

Helping professionals are intended to support people to make sustained improvements that matter to the lives of clients or patients. Historically, there have always been practitioners who operate from an "I know best" expert mode who decide what should matter to the client. However, this approach often proves limited in effectiveness, as it expects clients to implement advice addressing areas that are not aligned with their priorities or immediate concerns. When clients feel disconnected from their goal, often because the practitioner has set it for them, meaningful change is unlikely to occur.

On the other extreme, there are practitioners who interpret client- or patient-centred practice as “the client knows best”, focusing solely on helping clients develop their own solutions. This perspective overlooks the reality that if clients already knew how to solve their problems, they likely would have done so. Shifting the responsibility for the collaborative process entirely onto the client, while framing it as respect for the client’s agency and autonomy is misguided. It neglects the practitioner’s duty to contribute their specialised expertise, which the client is paying for, and ultimately fails to provide the support the client needs.

There is, of course, a happy medium between both practice models. This balanced approach values the knowledge, expertise, and context-specific experience that each party brings to the process. By pooling their respective insights, they can work together to develop a shared understanding of the client’s current challenges and develop actionable strategies the client can realistically apply to improve their situation. This collaborative model respects the client’s autonomy while utilising the practitioner’s expertise in a meaningful way.

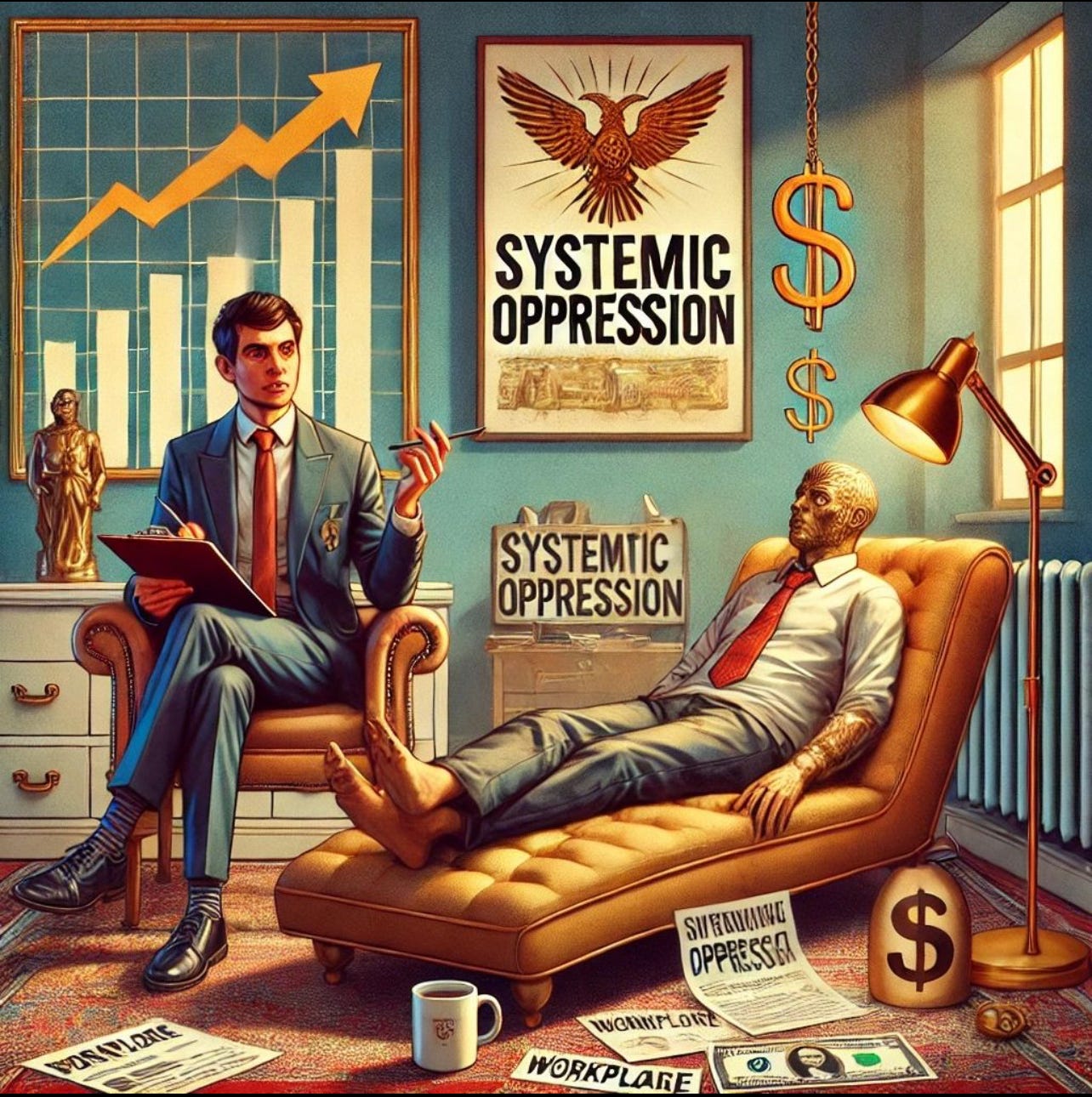

Since the introduction of concepts such as critical race theory, systemic oppression, and intersectionality into professional training and practice, many practitioners have felt compelled or pressured to incorporate these frameworks into their work. While such frameworks aim to help clients contextualise their experiences within broader systemic forces, they can sometimes shift the focus of therapy or support onto external factors beyond the client’s immediate control. This risks reinforcing a sense of helplessness or victimisation, detracting from the client’s ability to address the aspects of their situation that are within their power to change.

Effective practitioners understand the importance of balancing attention between external influences and the internal dynamics that shape a client’s perception of their challenges and area of life they seek to improve. While broader systemic forces can provide valuable context, it is equally crucial to explore how the client’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors influence their experiences and outcomes. A nuanced approach ensures the practitioner remains grounded in supporting the client’s capacity for personal growth and empowerment.

The concept of Saviourism is worth revisiting, particularly in the context of Saviour burnout. Saviourism often arises when a professional attempts to enact systemic change in environments resistant to their efforts. In such cases, the practitioner’s ideologies and activism-focused agenda often take precedence over the client’s needs, goals, and wellbeing, overshadowing the collaborative process under the guise of working for the client’s benefit. This dynamic undermines the practitioner’s effectiveness and shifts the focus away from truly supporting the client.

J.D. Haltigan and Ryan Rogers have a series of articles that go into depth about how mental health counselling training has become political instead of focusing on actual counselling.

Many trained helping professionals lack or have downgraded the basic skills necessary for helping people explore and examine their own perceptions and experiences. This shortfall has become more pronounced as social justice ideologies have seeped into professional practice, often shifting the focus away from individual inquiry and reflection.

We frequently encounter headlines and leap to conclusions about who the victims and perpetrators are, even when we have very little information. Instead of seeking clarity, we fill in the gaps using our assumptions, values, desires, and beliefs to craft a narrative that makes sense to us. This reflexive need to reduce uncertainty and discomfort transforms these incomplete stories into truths before we've gathered sufficient evidence to validate them.

Why do we do this? Because humans are inherently uncomfortable with uncertainty and the unknown. While some might claim to enjoy surprises, in reality, we only welcome the ones we find pleasurable or affirming. Surprising headlines, information, or events that challenge our worldview are often unconsciously reframed to fit the story we want—not the story of what actually is.

Our aversion to uncertainty stems from a sense of powerlessness and insecurity when we don't know how to respond in the moment. To regain control, we piece together fragments from our memories and past experiences to construct a reality that feels manageable, adjusting the narrative only when new information reinforces the feelings we’ve already decided upon. This process is less about seeking truth and more about protecting ourselves from emotional discomfort. Importantly, the story we conjure is heavily informed by the emotions evoked by the event itself, rather than by objective facts.

This is why empathy can also lead us astray. By prioritising how we feel over what we know, we risk adopting incomplete or inaccurate perspectives. As George Kelly explains through his Personal Construct Theory1, we interpret events through a system of mental constructs shaped by past experiences, often reinforcing preexisting beliefs instead of challenging them. This tendency underscores how easily misguided empathy can distort reality when we rely too heavily on feelings to guide our understanding.

Misguided empathy, or what’s also known as the dark side of empathy is well described in Gurwinder’s analysis on empathy as a driver of cruelty.

In the context of this article, misguided empathy corrupts truth and prioritises ideologically driven practices seen as corrective and liberating over evidence-based approaches proven to be effective in providing meaningful help. Rather than empowering the client to make meaningful change, the practitioner hinders progress by imposing and reinforcing a sense of victimhood onto the client. Ironically, the practitioner fails to recognise that they mirror the very societal and systemic oppressors they claim to oppose in their practice.

In 2023, I was delivering a lecture to a cohort of psychedelic facilitator trainees about the contributing factors to Saviour burnout within the practitioner community. This cohort consisted primarily of highly educated professionals with backgrounds in medicine, nursing, social work, psychotherapy, bodywork, traditional medicine practices, and others. These practitioners want to expand their ability to help clients by gaining credibility and tools in this excellent training program beyond what their conventional professional training had equipped them to provide. I used the term Saviour burnout to describe the phenomenon that occurs among facilitators entering the field out of a desire to provide underserved individuals with healing tools that should be accessible to everyone, not just those who can afford them.

I explained that the perception of an underserved person who gains access to psychedelic medicine is, in itself, a construct—an assumption shaped by specific identity markers. I also explored other terms frequently used to describe clients, highlighting how these often carry implicit assumptions of victimhood before the client has even shared their story.