Why bad feedback isn't about you

Spot the agenda behind the critique

In honour of my four years on Substack, I’m offering a discounted annual paid subscription until the end of the month. A subscription gives you full access to all my paywalled and archived articles, private 1:1 chats where we can discuss your challenging situations, discounts on upcoming workshops, and additional perks for subscribers. Offer expires August 31, 2025.

Much of what is labelled as feedback in professional environments is not designed to support growth. Within hierarchical systems it is often used to preserve control or to re-establish authority, operating less as a tool for learning than as a mechanism for maintaining dominance. For those who hold authority within a hierarchy, feedback can become a protective manoeuvre that is deployed when they feel unsettled or exposed, serving as a way of restoring equilibrium through control rather than through reflection or dialogue.

These behaviours can be understood as expressions of interpersonal narcissism, which reveal an inability to tolerate shame, vulnerability, or the loss of status. Rather than remaining with the discomfort of being challenged or uncertain, the person giving feedback directs their attention outward and seeks to manage the perceptions, emotions, or actions of others in order to protect a fragile self-image or preserve superiority. What I refer to as interpersonal narcissism can also be described as ego-defensive behaviour which emerges when a person feels exposed, threatened, or insecure and lacks the emotional maturity to tolerate that discomfort.

Many of these behaviours are expressions of interpersonal narcissism, which reveal an inability to tolerate shame or vulnerability and often involve protecting a fragile self-image or preserving a sense of superiority. Instead of remaining with the discomfort of being challenged or feeling uncertain, the person giving feedback seeks to restore control by managing how others think, feel, or behave.

Sometimes control is overt and dominating, but in many professional and relational settings it appears in a subtler form that is harder to challenge. This is what I call soft control. Soft control includes behaviour that looks polite, helpful, or even morally principled on the surface but is designed to preserve dominance and reinforce superiority within the interaction. It’s control that presents itself as care, a suggestion delivered as if it were a command, a compliment that also functions as a warning, or a boundary that operates less as a test of loyalty.

Soft control is particularly difficult to identify in the moment because it relies on plausible deniability and is easily concealed within established scripts of civility, professionalism, and shared values, yet its impact is real and significant as it generates confusion, undermines confidence, and strengthens hierarchies by drawing on language, tone, and performance rather than overt confrontation.

Understanding these dynamics makes it possible to see when feedback is being used less as a developmental tool and more as a means of stabilising hierarchy and regulating status. Ultimately it’s about power. This awareness allows us to resist being recruited into the roles we are being assigned and to respond with greater clarity about the function of the exchange.

This post explores what might be happening beneath the surface of unhelpful or poorly delivered feedback. It offers reframes that bring curiosity and insight to interactions that often leave people feeling dismissed or silenced. Recognising these behaviours for what they are allows us to assert boundaries and choose how we want to engage, while maintaining our values and our capacity for empathy.

Now, six years later, I am revisiting these examples with a psychodynamic lens. A psychodynamic perspective pays attention to how unconscious motives and defensive strategies take shape in relationships, influencing the exchange between the person giving feedback and the one receiving it. What might appear to be a professional comment can be a reaction to shame, an effort to restore power, or a way of discharging tension that arises in the moment of evaluation. In this sense, feedback is a dynamic in which both parties are managing insecurity, status, and vulnerability rather than a neutral judgment.

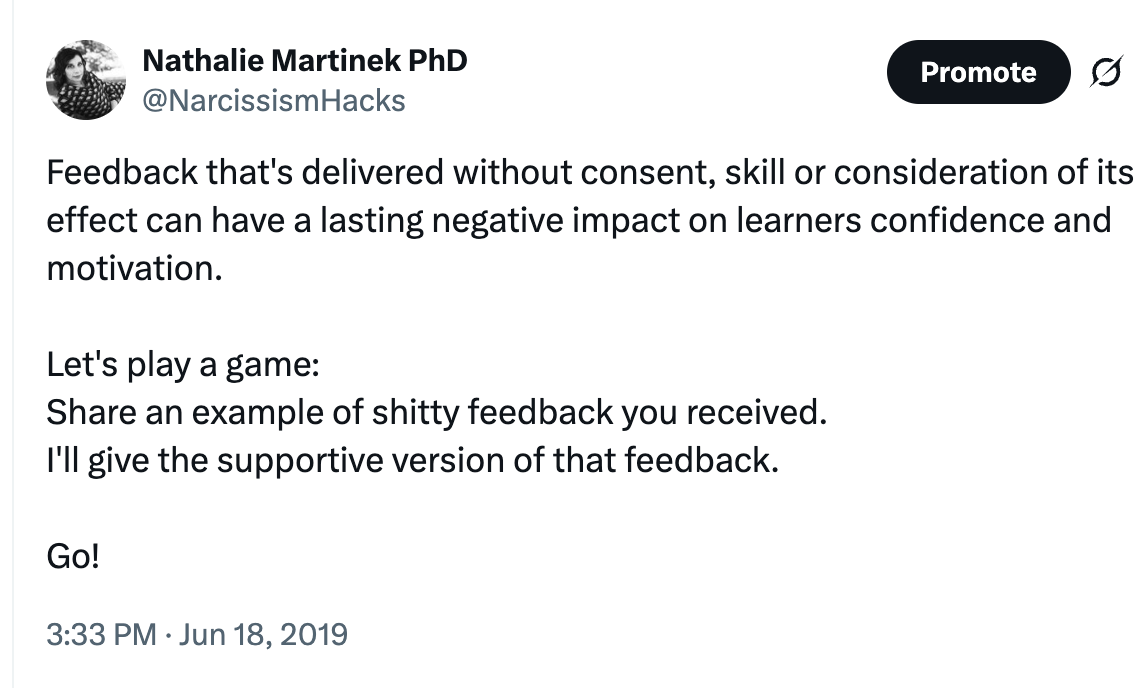

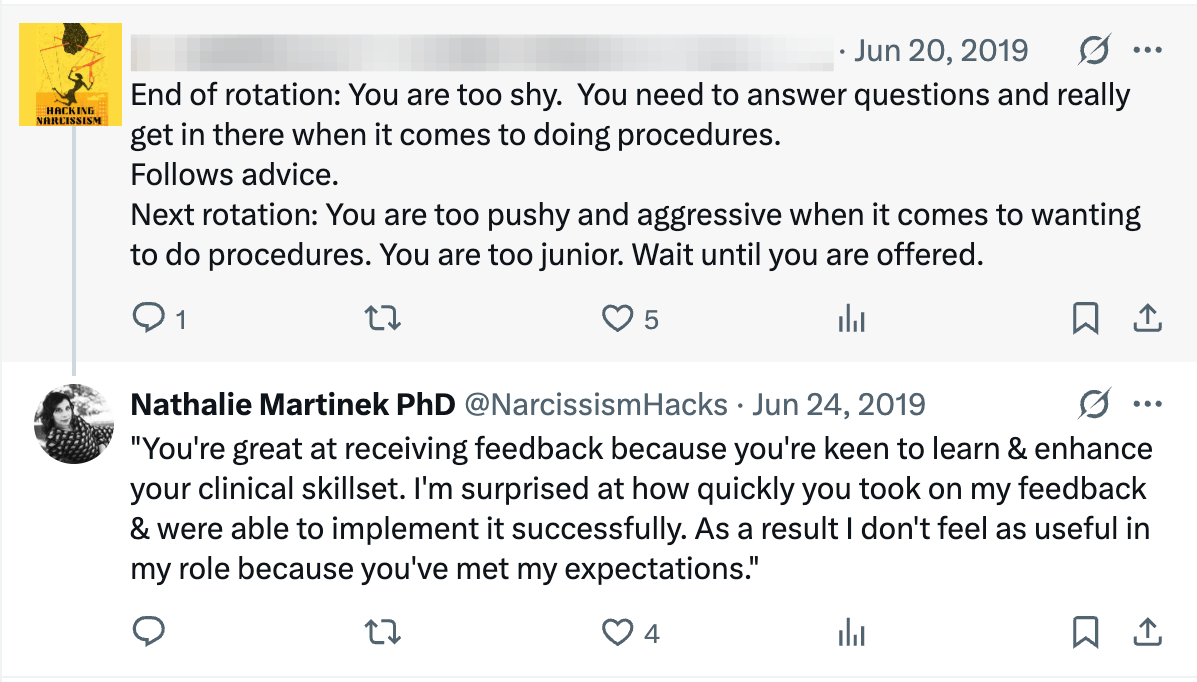

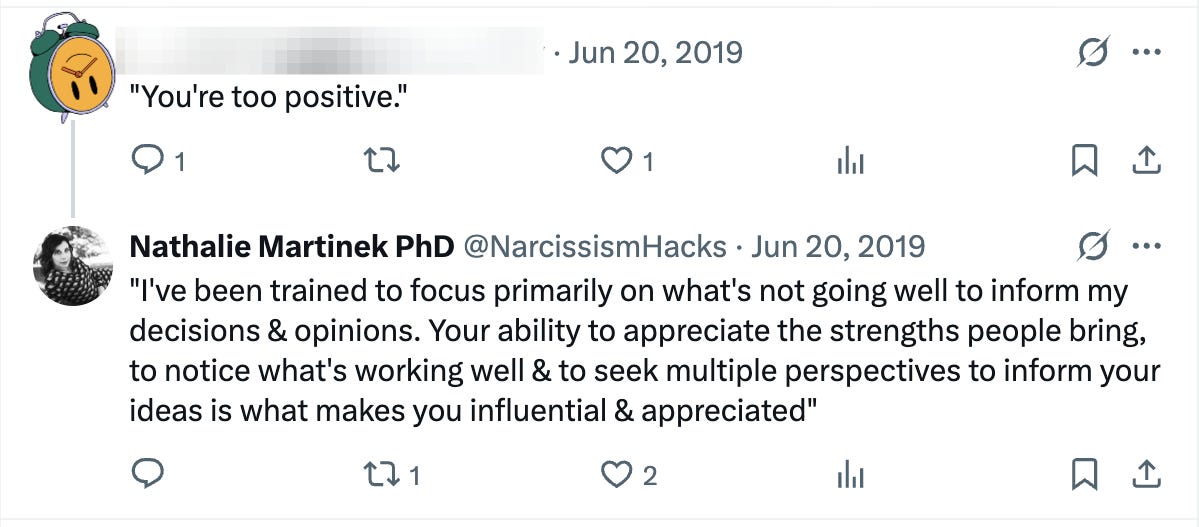

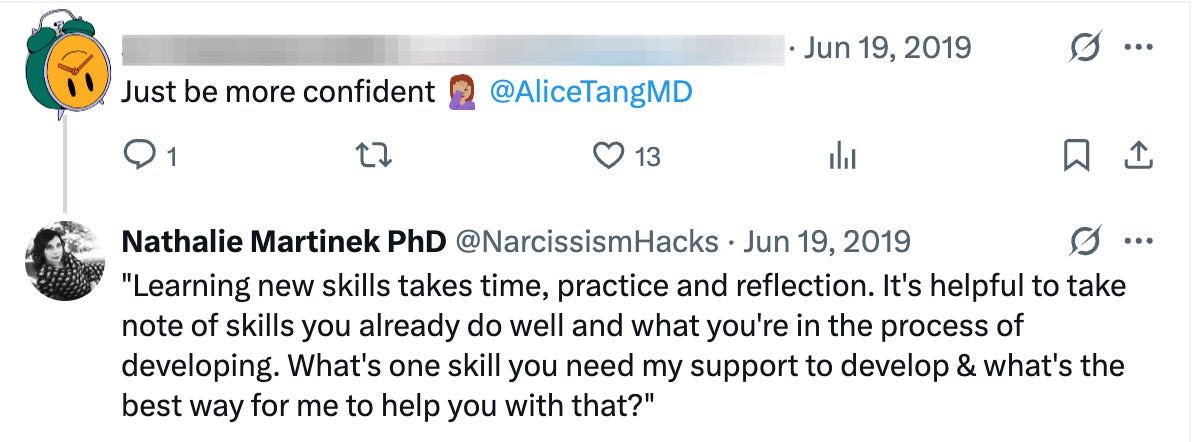

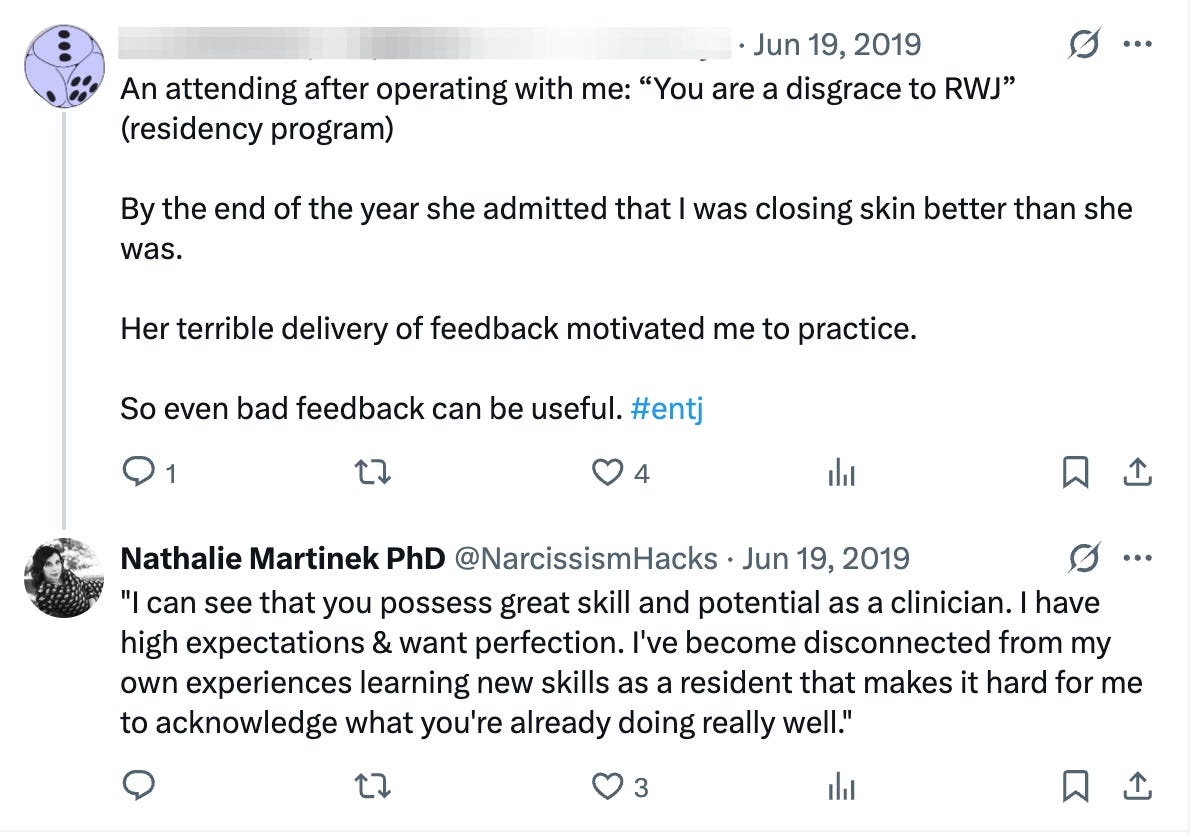

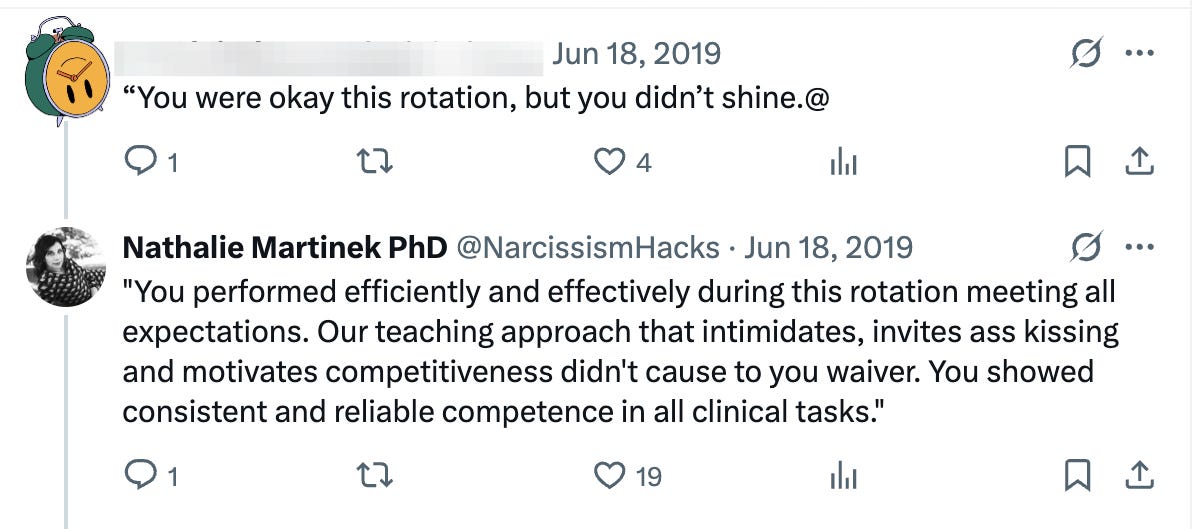

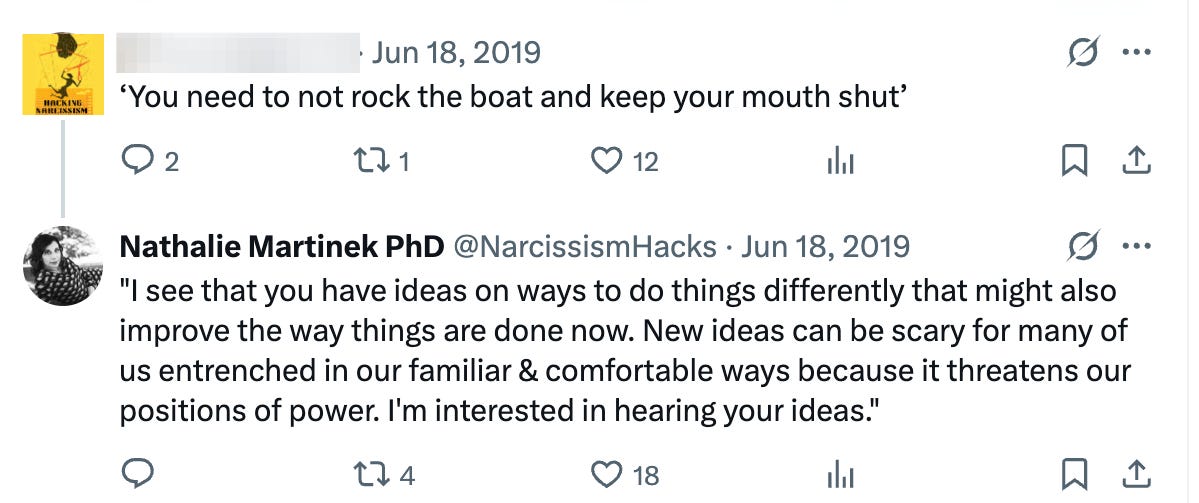

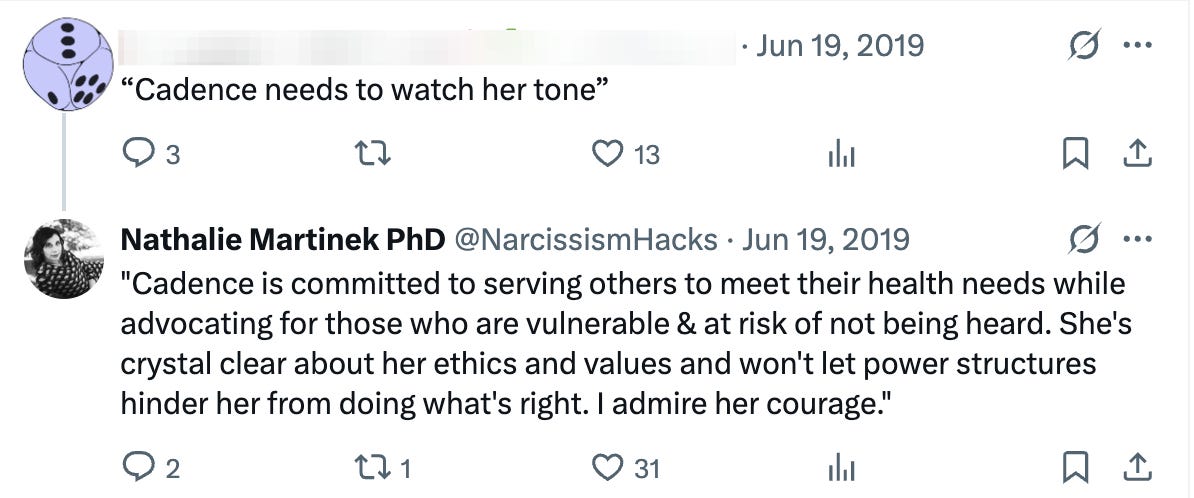

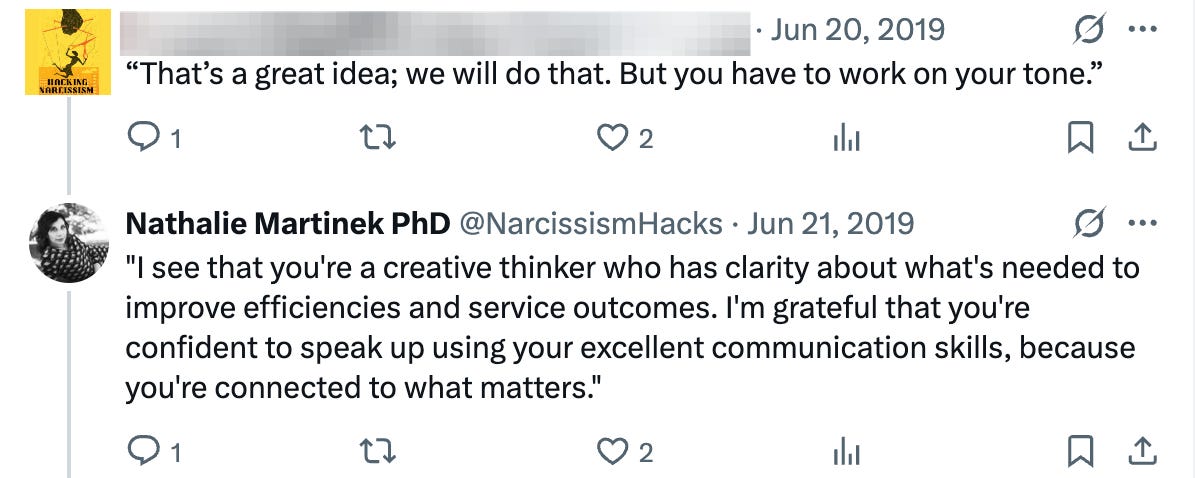

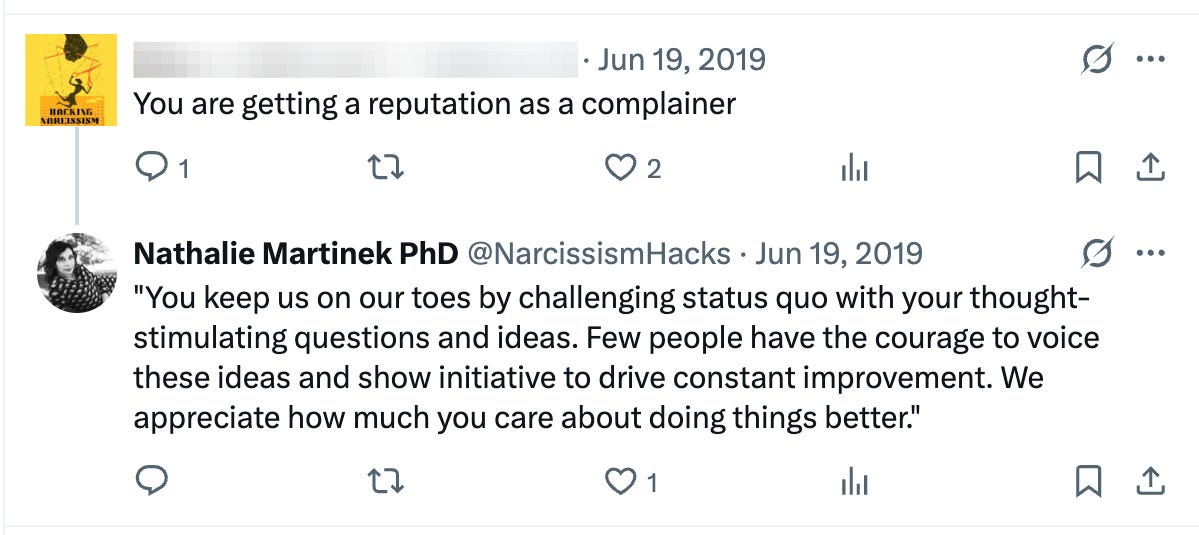

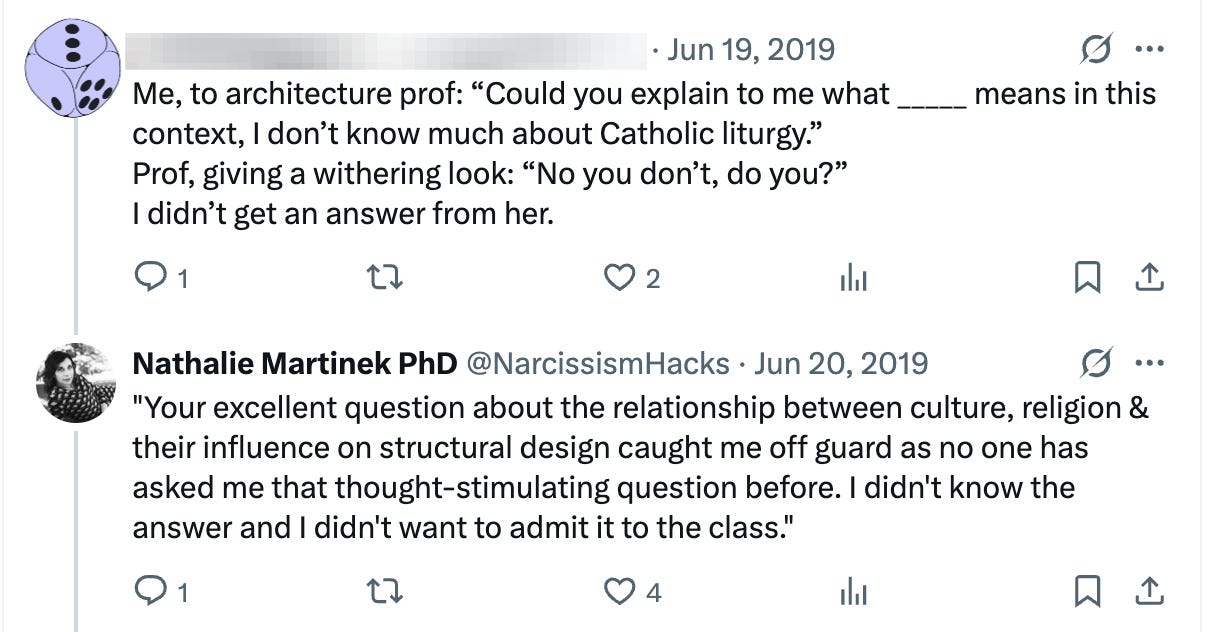

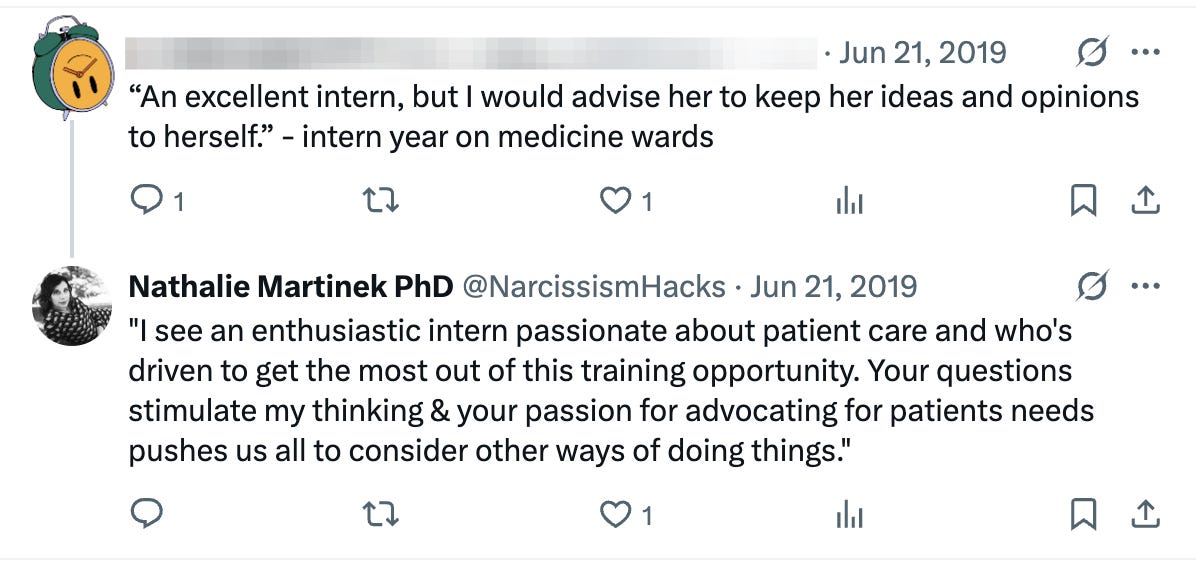

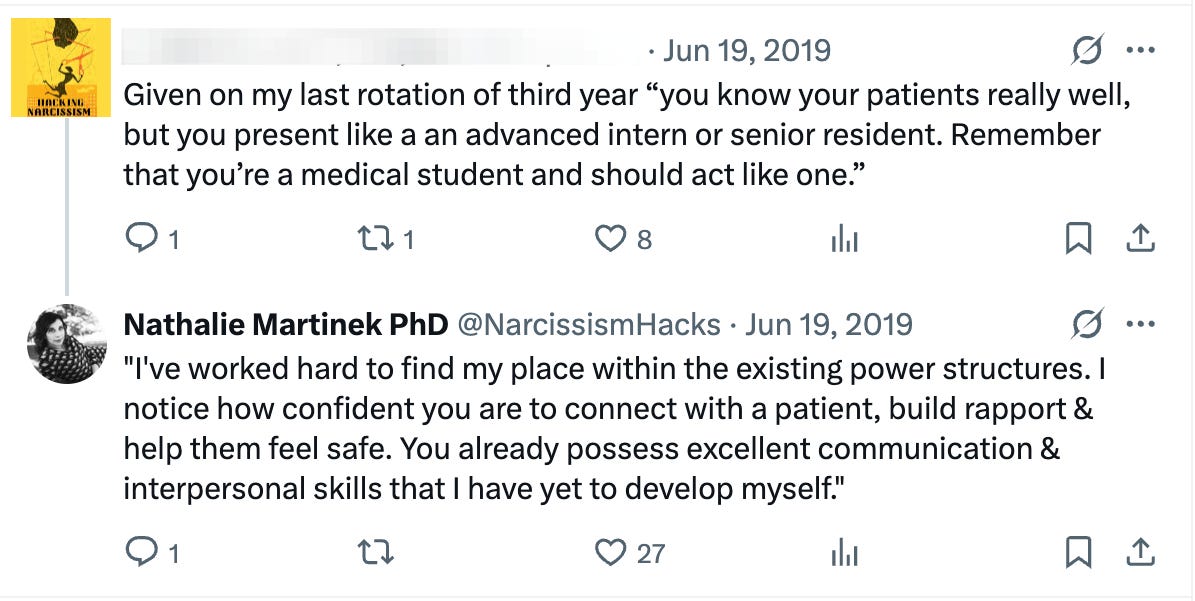

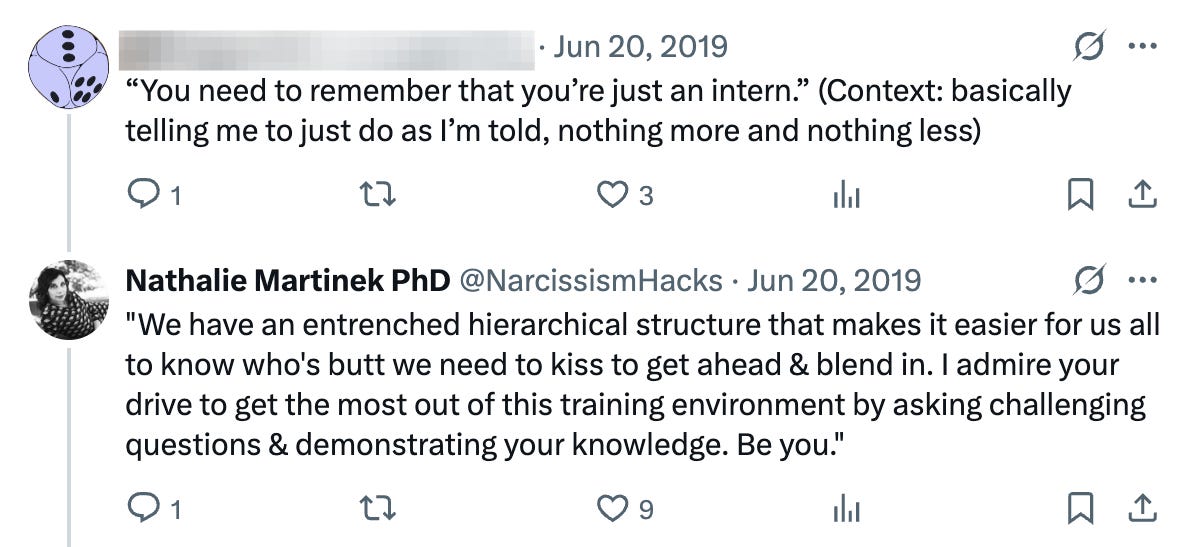

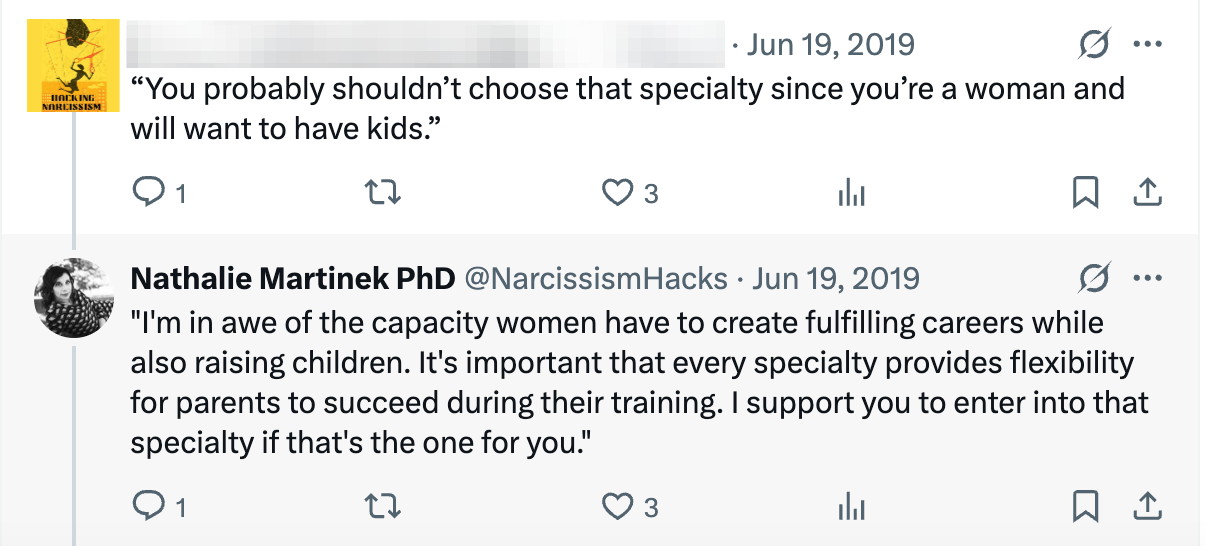

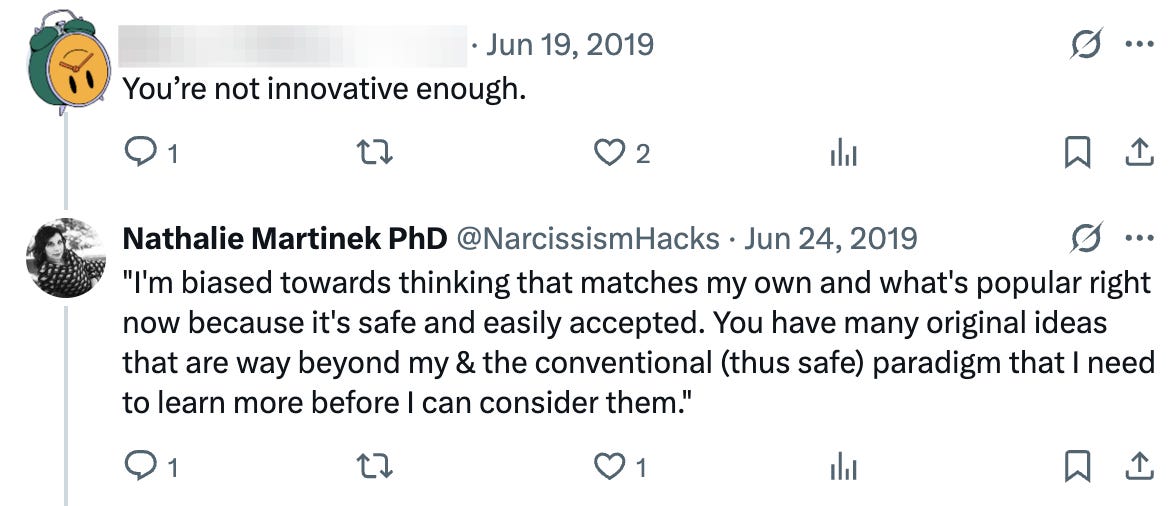

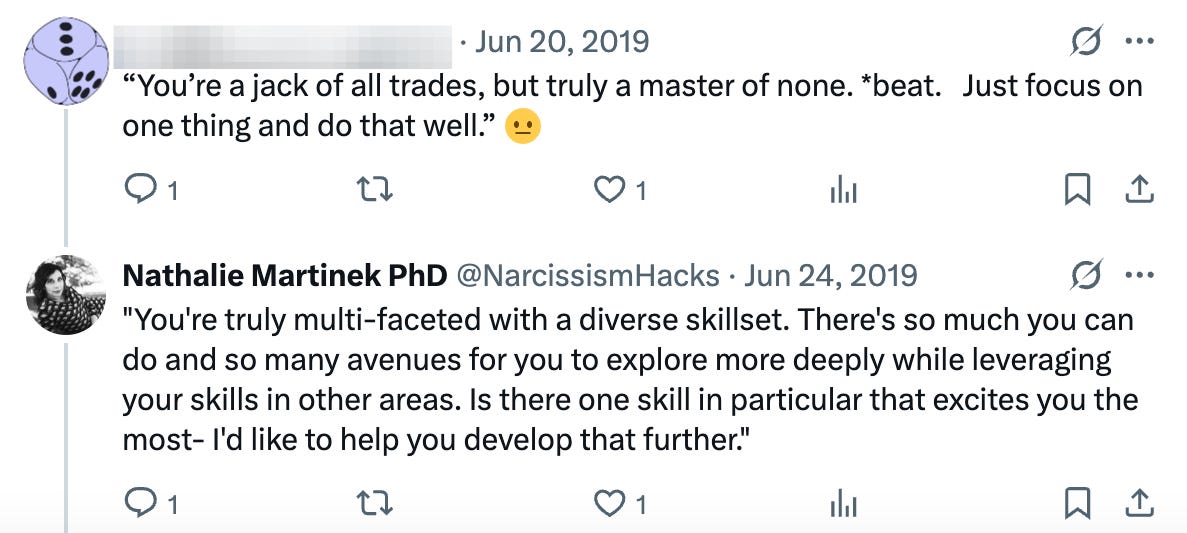

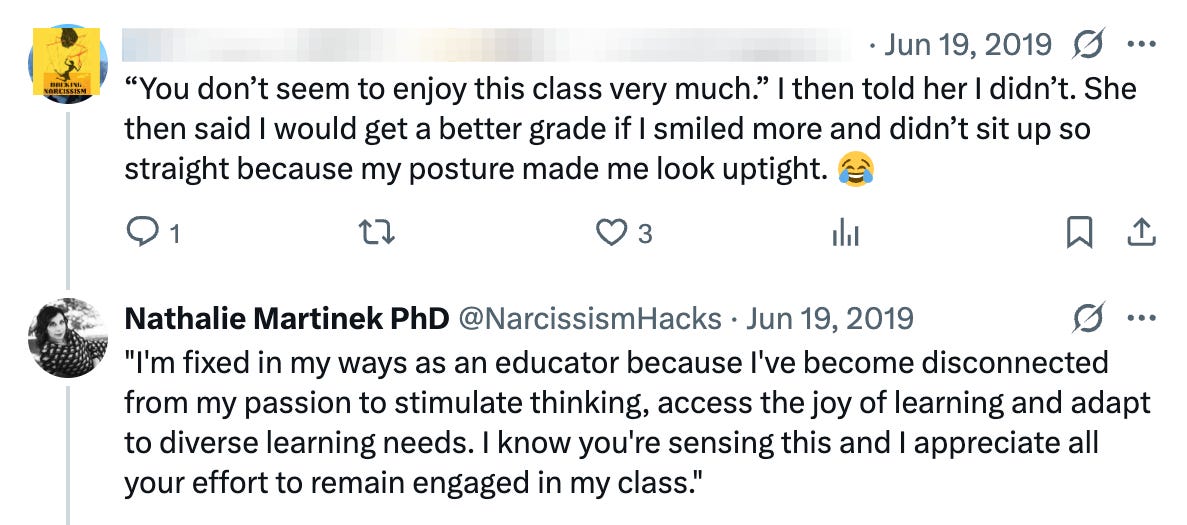

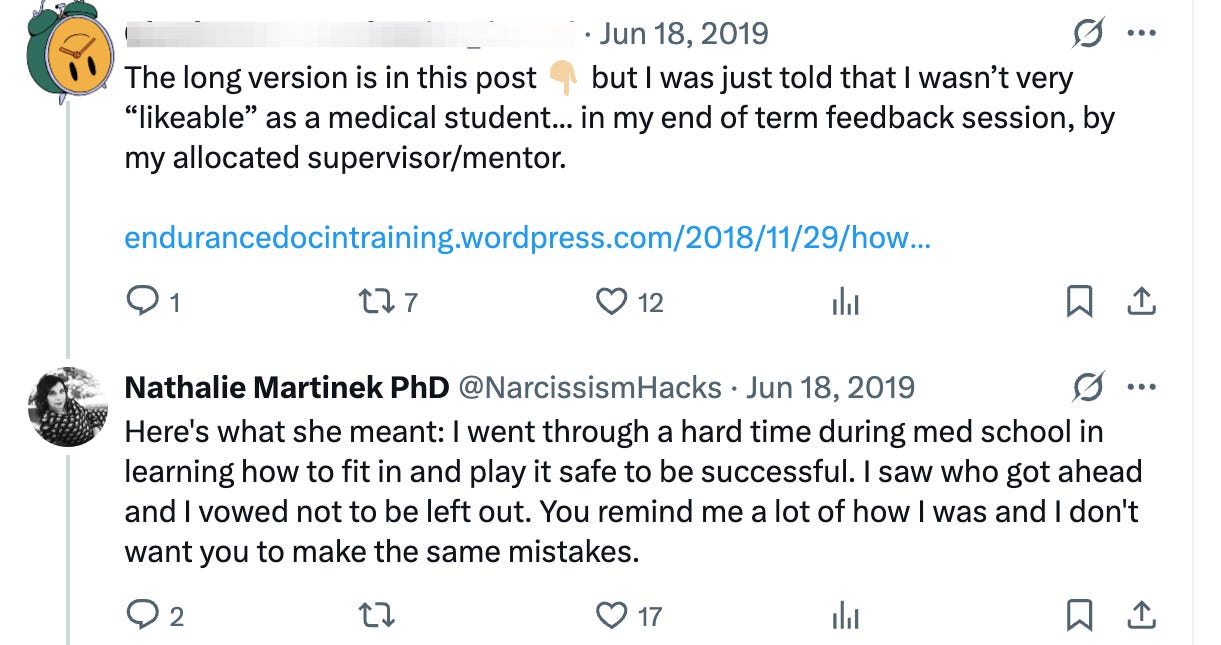

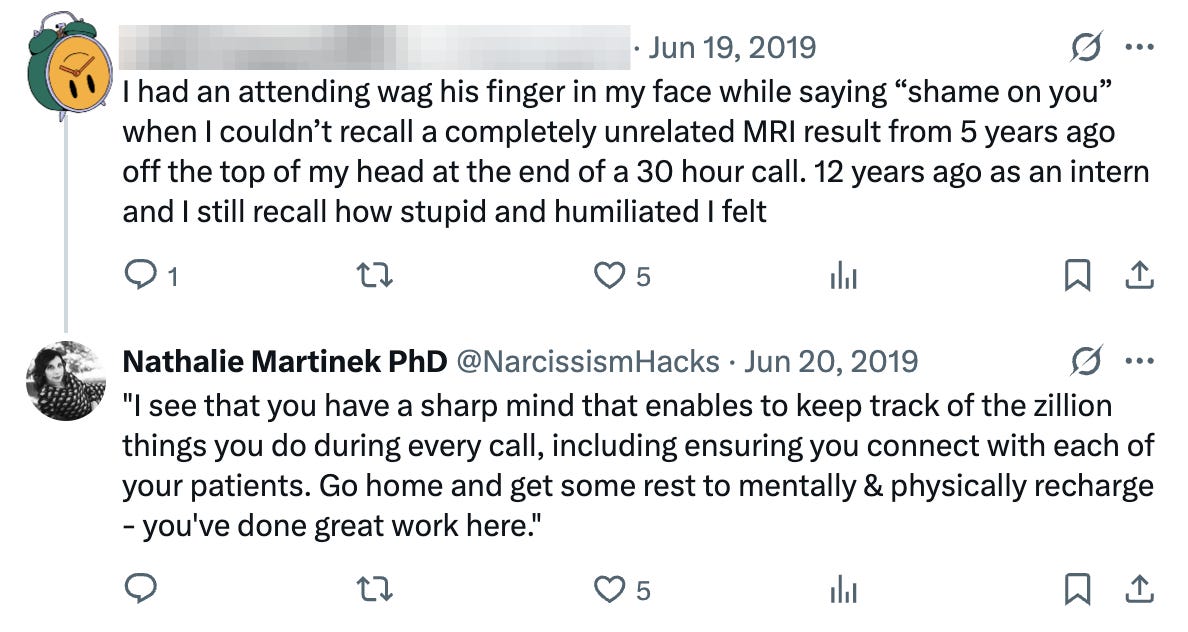

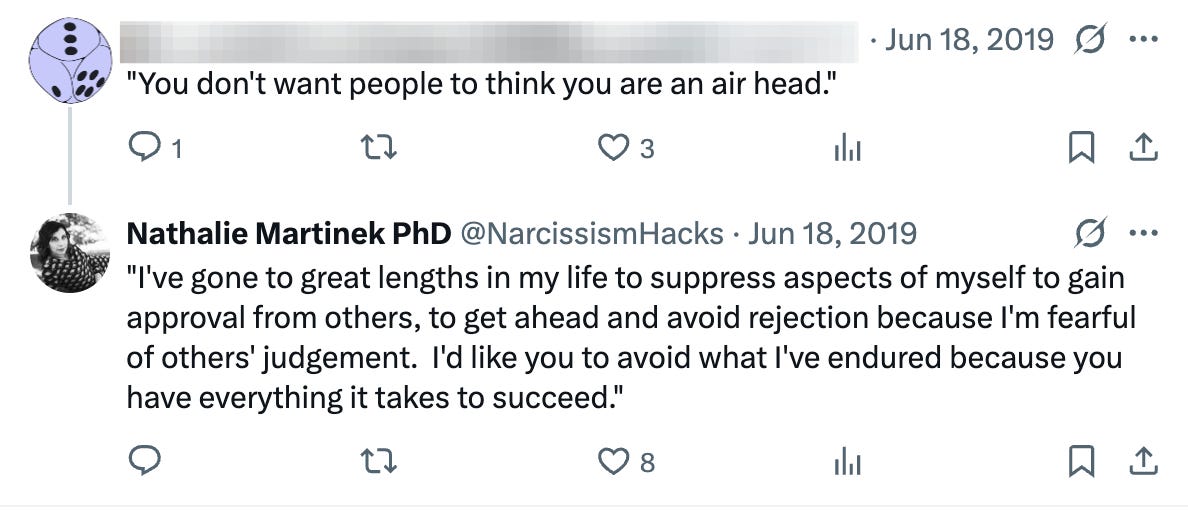

Consider this a feel good post reviving a thread from 2019, when I asked everyone to send me examples of unhelpful and mean feedback. In return, I offered to decode it into something more reasonable. This post resonated with many medical (and other professionals) because vague, hypercritical, and guidance-free feedback is a well-known feature of their rigid, hierarchical training environments.

Now, I’m not suggesting that in an apprenticeship model students always know best. Nor am I suggesting that unreasonable feedback should be tolerated just because someone is still learning. The issue is that most feedback is driven by emotion more than evidence, often shaped by the supervisor’s existing perception of the trainee, or by a lack of attention to and interest in what the trainee is actually doing. What gets framed as assessment is frequently biased or reactive. The problem is the lack of specificity and consistency in how feedback is delivered.

This is what motivated me to start the thread in the first place.

In my writing on difficult topics, I have often heard from readers that when shame was present the content brought relief or even felt healing, which was my intention in creating this feedback thread. By tapping into the unconscious drivers through narrative analysis of the feedback provider and pairing this with a compassionate narrative reframe, each example helped the recipient see the insecurities behind unhelpful or mean feedback. In doing so, what first felt wounding can instead be recognised as a reflection of the giver’s limits rather than an accurate description of the recipient’s worth.

I am reviving this old thread in case any of you, dear readers, need to exorcise the ghosts of harsh feedback past that still linger. My hope is that revisiting these examples helps set them free. The posts have been de-identified, though you are free to look them up on X if you wish, and they have been gathered here under different themes.

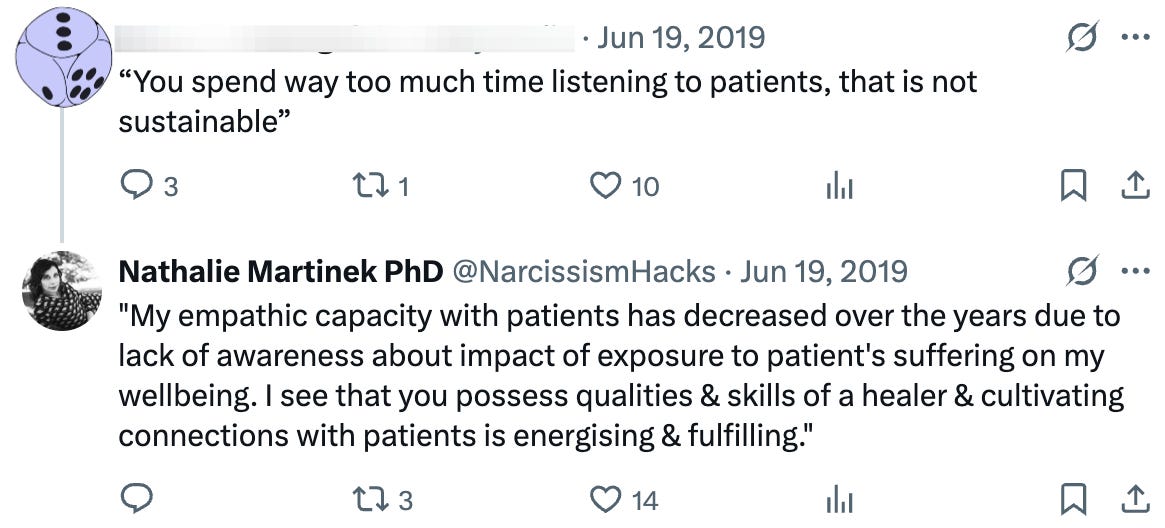

1. Too much / not enough

When feedback frames someone as too much or not enough it has little to do with their actual performance and much to do with the giver’s need to reassert control. Exaggerating strengths into flaws or reframing adequacy as deficiency allows the giver to steady their own authority and protect their position within the hierarchy, while keeping the recipient striving for approval they can’t ever fully secure. For the recipient the effect is destabilising because they’re kept off balance and left with the sense that whatever they do will be recast as wrong, which ensures the hierarchy remains intact by denying them any solid ground. Here are some examples from the tweets:

You’re too positive

You spend too much time listening to patients

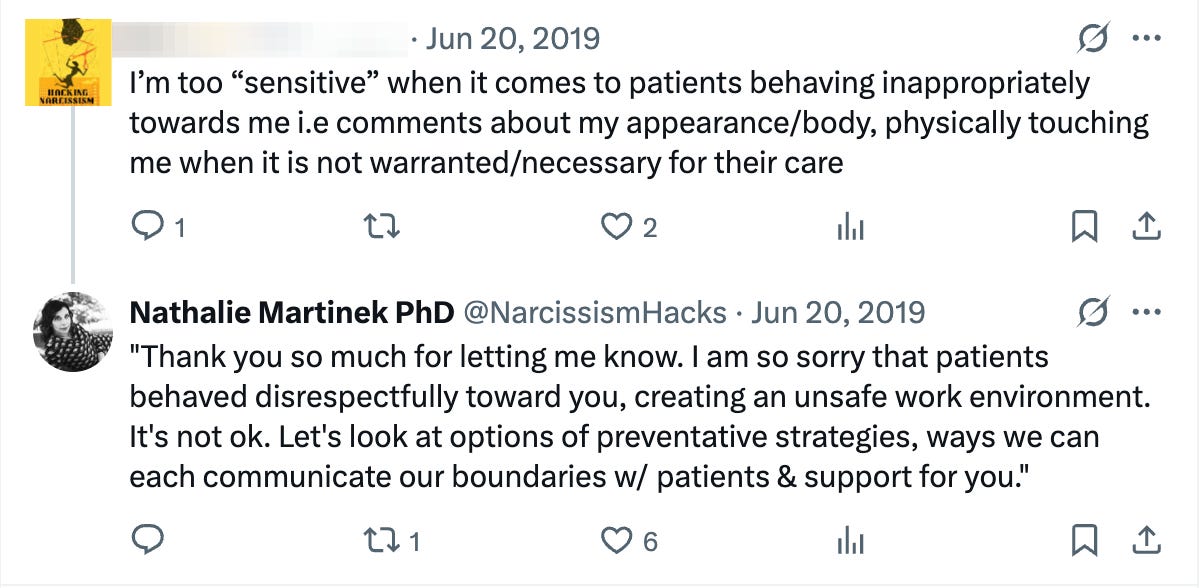

You’re too sensitive (about harassment or boundaries)

You’re too shy / You’re too pushy (contradictory double bind)

You’re not innovative enough

You’re not progressing as much as I’d like

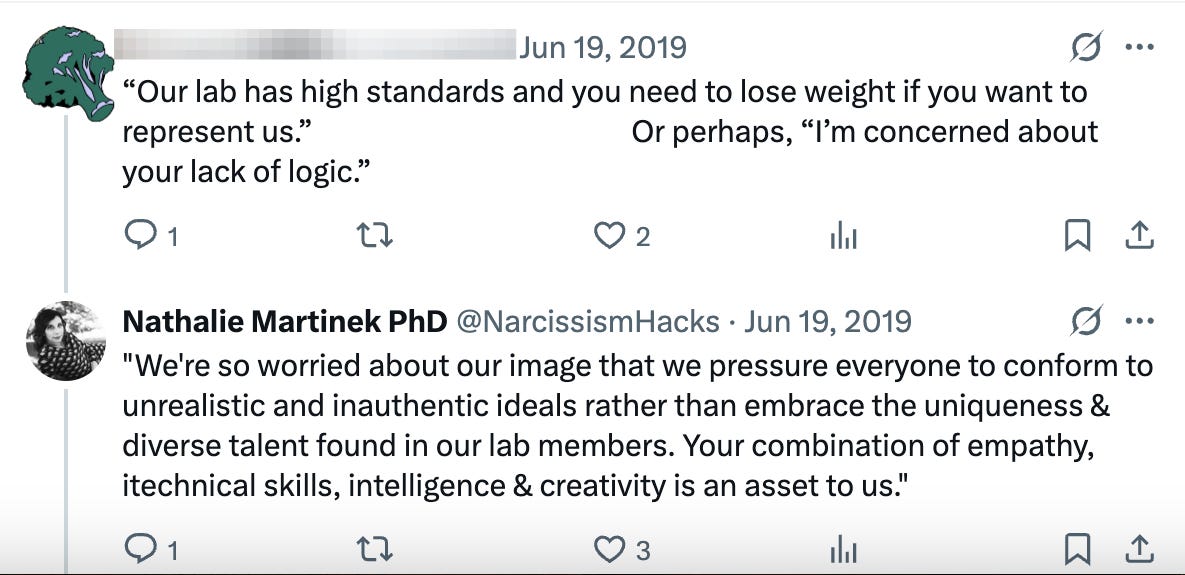

2. Vague, hollow, or unmeasurable

Vague feedback often emerges when the giver lacks the insight or confidence to guide someone directly, and instead of admitting uncertainty or offering concrete direction they fall back on hollow phrases or noncommittal judgments that preserve their authority by keeping the recipient guessing. For the learner, this creates a cycle of confusion and self-doubt where energy is wasted trying to decode what can’t be clarified, which turns vagueness into a tactic of control that stabilises hierarchy by obscuring responsibility.

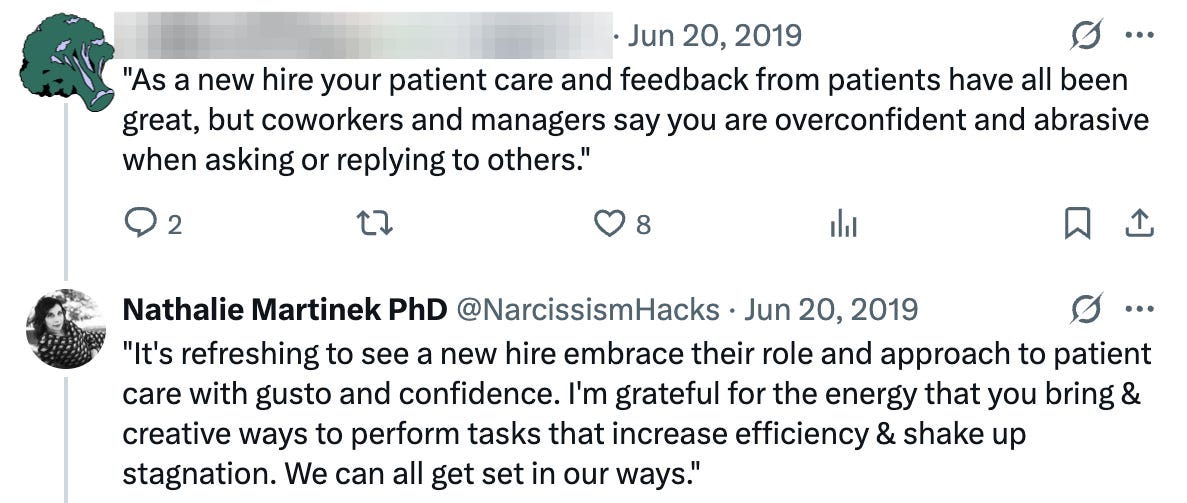

3. Tone policing and silencing

Criticism of tone or style often arises when the substance of what’s being said is perceived as threatening, and the giver manages their discomfort by shifting attention away from the ideas themselves and onto the manner of delivery, which allows them to avoid engagement while still maintaining the upper hand. For the recipient the effect is silencing because they learn that even expression itself can be policed, which discourages candour and keeps them in a position of submission within the hierarchy.

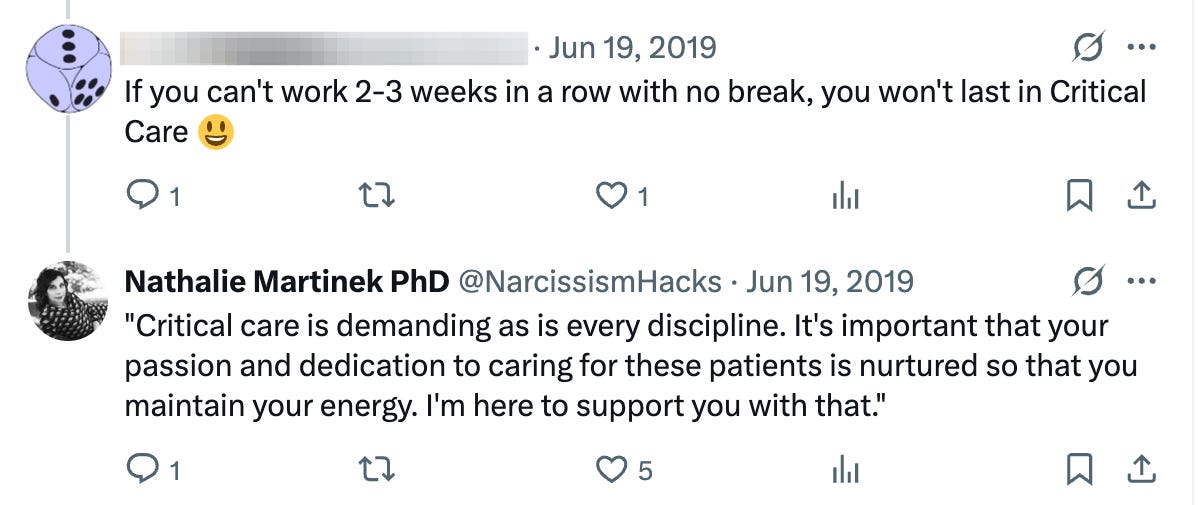

4. Status preservation and hierarchy enforcement

Much of what passes as feedback functions less as guidance and more as a reminder to know your place, surfacing when the giver feels their authority is under threat and seeks to restore order by forcing the recipient back into a subordinate role. In these moments feedback protects fragile egos and hierarchies rather than supporting development, and for the recipient the cost is discouragement and self-erasure because initiative, confidence, and autonomy are cast as threats to control instead of recognised as capacities to be strengthened.

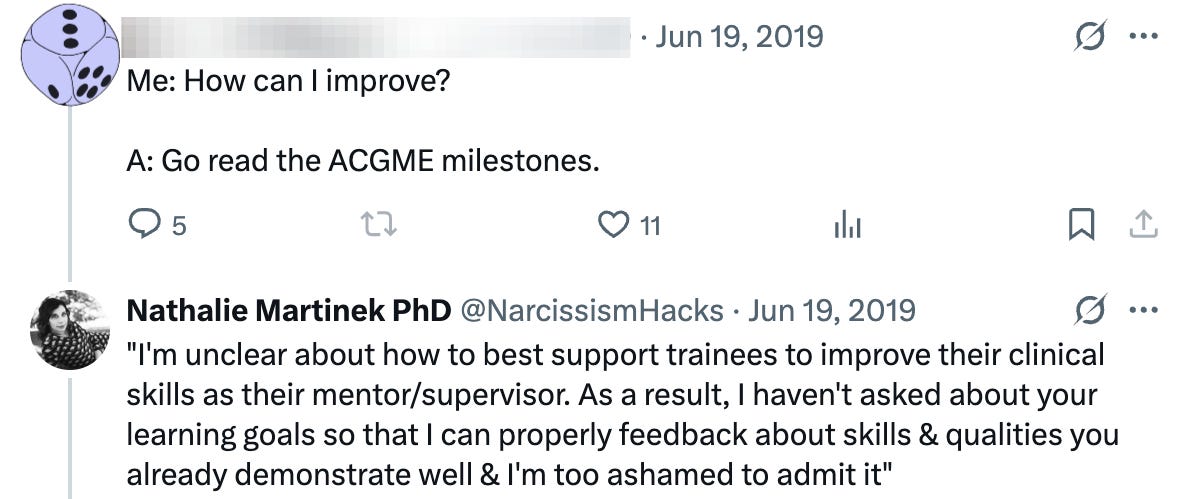

5. Criticising appearance or personal qualities

When feedback shifts to appearance, personality, or style it reveals the giver’s difficulty with tolerating their own vulnerability and redirects attention away from the content of the work. Policing how someone looks, speaks, or carries themselves turns personal bias into the appearance of professional judgment and allows the giver to restore a sense of control without having to engage with substance. By focusing on surface qualities the exchange is framed around impression management rather than performance or learning, which stabilises hierarchy by keeping the recipient busy monitoring themselves instead of developing their skills or advancing their ideas. For the recipient the effect is corrosive because it encourages shame and self-consciousness while also leaving them uncertain about whether they are being evaluated on their competence or on traits that have nothing to do with the work.

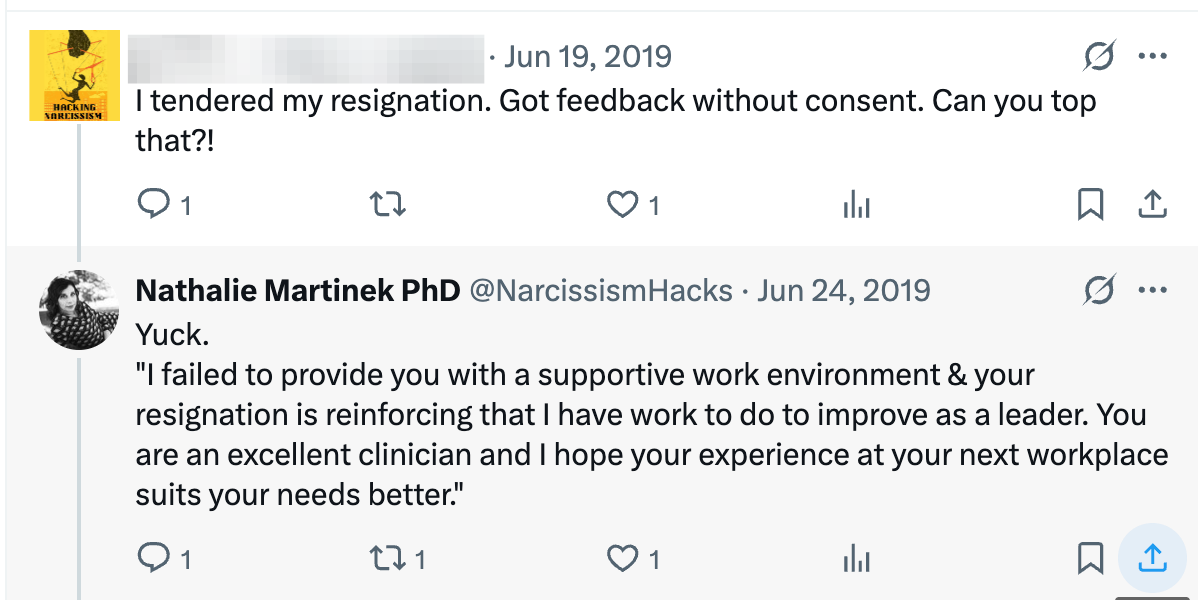

6. Withholding support / lack of self-awareness

Sometimes feedback is used to cover the giver’s own inadequacy. Rather than acknowledge their limits as mentors, they deflect responsibility with empty advice, vague references to bureaucracy, or unsolicited judgments offered only after someone has resigned. These tactics shield them from confronting shame while allowing them to appear authoritative and in control. For the recipient the result is a sense of abandonment and frustration because their effort to learn is met with avoidance instead of guidance, leaving them to carry the labour of improvement and the blame for any shortcomings.

You can refine your own response and avoid taking on their projections when you’re able to perceive the emotional forces driving their feedback. This turns the exchange from one where you’re pressured to accommodate their insecurity into one where you assert your authority. I designed The Little Book of Assertiveness (shameless plug) with this exact aim in mind by showing how to hold your ground when someone turns feedback into a power play or a status game.

Harsh feedback, especially when it works to preserve hierarchy, often carries both envy and shame. The person giving feedback might feel unsettled when a junior or colleague displays of authority through their competence and confidence that they can’t easily match. In some cases, the target might actually be arrogant warranting criticism. More often, however, the target is simply capable, and that competence stirs shame in the one who is meant to be the mentor. The defensive response to this sense of inadequacy is envy, which drives efforts to reassert hierarchy and preserve status. The recipient also brings shame from insecurity into the exchange, whereby a sharp comment can land with disproportionate force when it touches an existing point of doubt or vulnerability. This is why even poorly grounded feedback can sting, since an aspect of it might be true and simultaneously affirms a pre-existing uncertainty.

Seen this way, feedback is rarely a neutral judgment. It is often an interaction between two insecurities: envy and shame in the giver, and shame and self-protection in the recipient. This does not mean all feedback should be dismissed. Some comments contain signals that can support growth, while much of it is noise produced by projection and status regulation. The task is one of discernment: to recognise what clarifies performance or direction, and to set aside what reflects the limits of the giver.

Seen this way, feedback is rarely a neutral judgment. It is an interaction between insecurities, with envy and shame in the giver and shame and self-protection in the recipient. The tweet exchanges collected here make those dynamics visible. What looks like guidance often functions as soft control, which is a way to manage perception and re-establish authority rather than to foster growth. Some comments may still contain signals that support learning, but much of what circulates as feedback is projection and status regulation. This is why discernment is required to recognise what genuinely clarifies performance or direction while suspending what reflects the limitations of the one giving the feedback.

Hack narcissism and support my work

I believe that a common threat to our individual and collective thriving is an addiction to power and control. This addiction fuels and is fuelled by greed - the desire to accumulate and control resources in social, information (and attention), economic, ecological, geographical and political systems.

While activists focus on fighting macro issues, I believe that activism also needs to focus on the micro issues - the narcissistic traits that pollute relationships between you and I, and between each other, without contributing to existing injustice. It’s not as exciting as fighting the Big Baddies yet hacking, resisting and overriding our tendencies to control others that also manifest as our macro issues is my full-time job.

I’m dedicated to helping people understand all the ways narcissistic traits infiltrate and taint our interpersonal, professional, organisational and political relationships, and provide strategies for narcissism hackers to fight back and find peace.

Here’s how you can help.

Order my books: The Little Book of Assertiveness: Speak up with confidence and The Scapegoating Playbook at Work ebook

Support my work:

through a Substack subscription

by sharing my work with your loved ones and networks

by citing my work in your presentations and posts

by inviting me to speak, deliver training or consult for your organisation

So what I've been experiencing is where I point out issues for months and suddenly I am the one be lectured for the issues I pointed out in the first place!!! What in the hell is that?!?!

Thank you for this. You described my life as a medical student and resident. Always poor feedback.