The Scapegoating Playbook at work

How competent people are broken down to protect dysfunction

This post may be truncated in your inbox. For the full experience, read it on Substack.

Scapegoating at work and in other social groups, including families, is a topic that always seems to hit a nerve. It brings up strong emotions for a reason. Being scapegoated is a confusing and often soul-crushing and even traumatising experience, and most people don’t realise it is happening until they are already deep into the pattern.

I have written about scapegoating in professional settings, why it happens, and how to step out of the role once you recognise it.

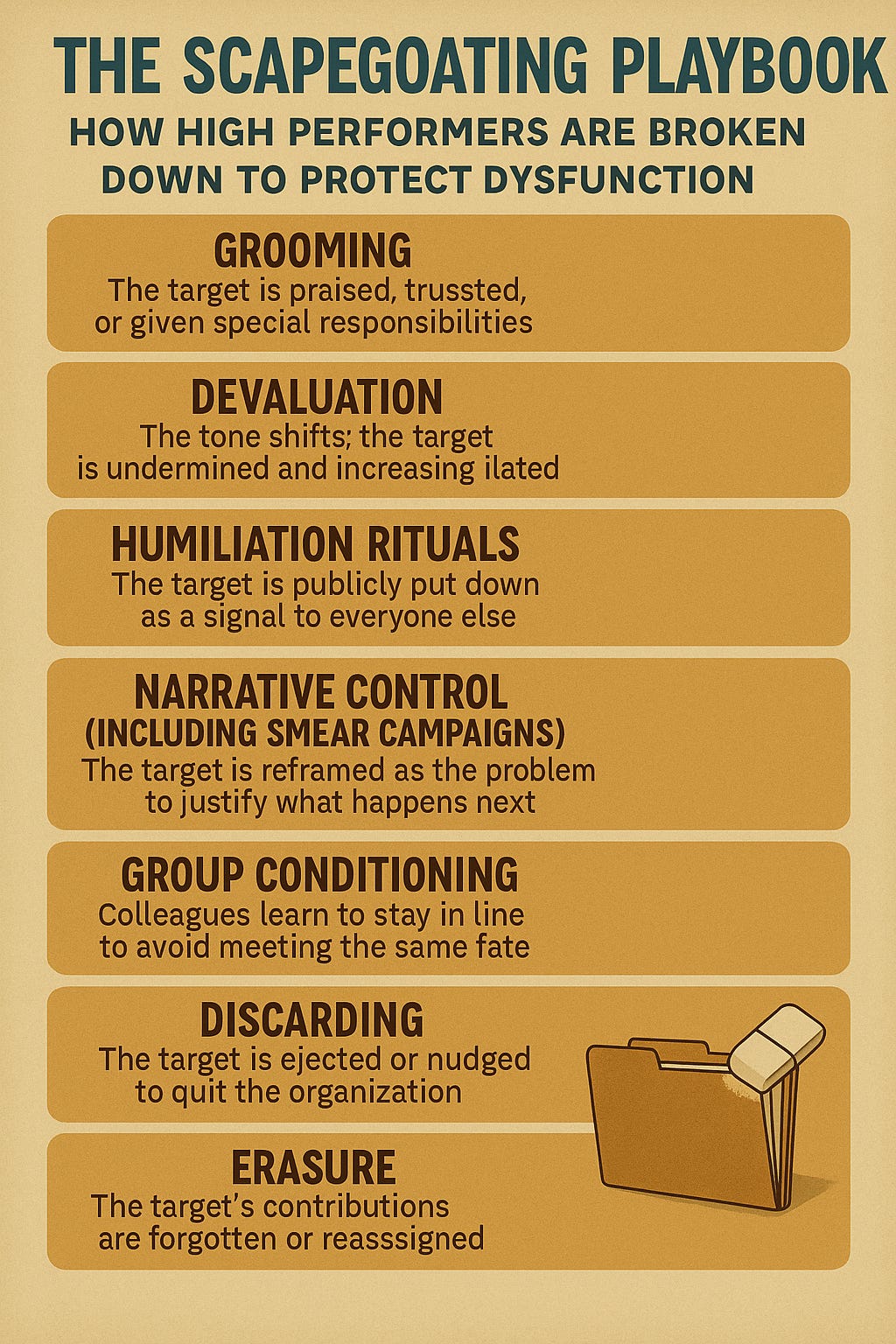

I thought it would be helpful to provide a breakdown of the predictable and sometimes overlapping stages of scapegoating, to help you identify whether this is happening to you and which stage you might be experiencing. It follows a recognisable pattern, which is why it is often described as a playbook. I am not the first person to outline a Scapegoating Playbook and I will not be the last. There are many versions, and this is the one I have put together based on my own observations and experiences with the scapegoating process.

There are eight stages in the playbook. Seven are carried out by the scapegoating instigator and their Flying Monkeys (enablers), while the final stage is more within the control of the targeted person.

This piece offers a brief overview of each stage. I will also be releasing an eBook that includes more than thirty posts featuring scapegoat narratives and images that illustrate how these stages unfold. It is designed to help you recognise if this is something you are facing at work, in your family, or in any other group dynamic.

This post also brings together ideas and writing I have shared previously that explore each of these stages in more depth, for those who want to go further.

Scapegoating thrives in narcissistic systems — environments that prioritise image, control, and loyalty over reflection, transparency, and repair. These systems depend on unspoken rules, emotional containment, and the quiet removal of anything that challenges the dominant narrative.

The 8 stages of the Scapegoating Playbook at work

Grooming and Idealisation

Grooming follows the first stage in the classic cycle of abuse: idealisation, where the target is elevated, admired, or seen as uniquely valuable before the system begins to devalue and eventually discard them. The target is welcomed with warmth, enthusiasm, and a level of early trust that feels both validating and surprising. They are praised for qualities that appear to align with the organisation’s values or the unspoken ideals of the group. This often includes invitations to participate in high-visibility tasks, casual gestures of inclusion, or praise that suggests their presence is especially appreciated. These moments create a sense of safety, belonging, and purpose that feels earned.

The connection feels genuine, but it is often based more on projection than on a full understanding of the individual. The system or person doing the grooming may not be aware of this. They are drawn to the target because of what they appear to represent: competence, loyalty, alignment, or shared ideals. The praise feels personal, but it is often rooted in how well the target reflects or reinforces an idealised version of the team, leader, or culture.

This early stage is rarely about conscious manipulation, unless the behaviour is being driven by someone with narcissistic traits or other dark triad characteristics, in which case the idealisation may be more deliberate and strategic. It is about unconscious role formation. The target is not being seen as they are. They are being positioned into a role based on the needs, expectations, or insecurities of those around them. These early dynamics create emotional bonds that feel mutual, but that often carry unspoken conditions. Once those conditions are broken, the tone can shift quickly and without warning.

Learn about yourself if you’ve been a serial Scapegoat

Devaluation

Devaluation begins when something about the target creates discomfort or tension within the system. This may relate to their confidence, visibility, emotional tone, communication style, appearance, or even the steadiness with which they carry themselves. It is not always about what the person does, but more often about what they represent or evoke in others. Their presence begins to feel out of step with the emotional climate or unspoken norms of the group.

The tone toward them starts to shift. Praise becomes less frequent or disappears entirely. Communication may become colder, delayed, or inconsistent. Feedback, when offered, tends to be vague, difficult to interpret, or subtly corrective. The target often responds in good faith. They try to steady the dynamic by working harder, softening their delivery, seeking clarity, or increasing their emotional labour.

The shift often reflects the activation of the workplace’s immune system. Something about the target has registered as a threat to the group’s emotional, social, or political balance. This threat may have nothing to do with intention or behaviour. It may be the result of presence, insight, visibility, tone, or a refusal to perform what others have come to expect. The group begins to respond not through confrontation, but through withdrawal and quiet distancing, as if expelling something it cannot comfortably metabolise.

These efforts rarely change the outcome. Devaluation is often a defensive reflex. The system begins to protect itself by pulling back connection and trust from someone it now experiences as a threat to cohesion, control, or comfort. The target is left confused and off-balance. They may become overly responsible for the relationships around them, while slowly losing their sense of stability and belonging. The rules have changed, but no one names it, and no one explains why.

Workplace immune response

Introduction to the Narcissistic Family System

When giving feedback results in devaluation

Humiliation rituals

Once the scapegoat has been identified, the breakdown of their standing within the group becomes visible. The target might be corrected in meetings, excluded from communications, or subtly undermined in ways that are observable to others. These moments are rarely accidental as they function as social signals that reinforce existing power structures and communicate to the group what is and is not acceptable.

Humiliation can take many forms. It can show up as a joke at the target’s expense, a pattern of being talked over, a dismissive glance, or the absence of acknowledgment when they speak. It may look like strategic silence, being left out of decisions, or having their contributions attributed to someone else. These gestures are often delivered in ways that appear minor in isolation but accumulate into a clear message.

The purpose is not only to destabilise the target but also to send a warning to others. These rituals demonstrate the social cost of challenging authority, questioning group norms, or simply standing out in a way that makes others uncomfortable. When the group witnesses this behaviour and does not intervene, the treatment begins to feel normal. Over time, it is seen as justified, even when no clear reason for the shift has been named.

Narrative control and smear campaign

Narrative control begins when a new story about the scapegoated person starts to take shape. It does not require direct accusations or outright lies. Instead, it relies on suggestion, repetition, and selective interpretation of events. The target is gradually recast as the problem. They might be described as too intense, difficult to work with, overly sensitive, or resistant to feedback. These descriptions are often vague but emotionally charged, which makes them difficult to challenge directly.

These narratives do not tend to appear in formal settings. They spread through casual one-on-one conversations, private debriefs, or expressions of concern that present the speaker as thoughtful and reasonable. The person driving the narrative often does not act alone. They draw others in, sometimes unintentionally, by framing the story in ways that activate group loyalty, anxiety, or moral positioning. Once others accept the narrative, they begin to repeat and reinforce it, often without checking its accuracy or asking questions.

This process does not happen to clarify what occurred. It happens to protect the group from discomfort and to preserve the integrity of the system’s self-image. Reframing the scapegoat as the source of tension allows the group to justify exclusion without examining the conditions that made the exclusion necessary.

Group conditioning

As the scapegoating process continues, the group begins to adjust its behaviour in response. Colleagues who previously supported the target may withdraw. Some do so to protect themselves, while others begin to align with the person or people who appear to hold power. Individuals who might normally speak up often remain silent, not because they are indifferent, but because they do not know how to respond without risking the same treatment.

Bystanders tend to default to behaviours that reduce their own sense of threat. Some avoid conflict entirely. Others work to smooth over tension or subtly distance themselves from the scapegoated person. These are adaptive responses that prioritise psychological and social safety, even if they come at the expense of integrity or connection.

Over time, this behaviour becomes routine. The group learns, often without realising it, that protecting one’s position matters more than protecting one another. What begins as individual self-preservation gradually becomes collective behaviour. This quiet shift reinforces the scapegoating pattern and allows it to embed itself as part of the culture.

Upstanders and scapegoating

How groupthink sustains bully denial

Discarding

Discarding begins when the target is no longer useful to the system in emotional, political, or social terms. The process unfolds quietly. The person may notice they are being left out of meetings, excluded from decisions, or slowly stripped of responsibilities. These changes are rarely acknowledged or explained. The withdrawal is subtle and often appears unintentional, which makes it more difficult to challenge or name.

There is no clear rupture. Instead, the target is left to make sense of reduced access, delayed responses, and a growing sense that their presence is no longer welcome. The system avoids direct conflict by withholding engagement. It waits for the person to burn out, give up, or remove themselves.

To those on the outside, the change might look like a neutral transition or a quiet exit. To the person being discarded, it feels like being erased in real time. They are no longer part of the story, but no one says why. The organisation or group moves on without ever acknowledging what was lost or how it was made to happen.

Erasure

Erasure begins while the scapegoated person is still present. Their input is overlooked during meetings. Their contributions are minimised, dismissed, or quietly attributed to others. They are excluded from decisions that directly impact their work, and they may notice that people speak about them in the past tense or refer to their work as if they are no longer actively involved.

This stage does not rely on confrontation or open rejection. It works through omission instead. The scapegoated person is gradually removed from relevance, responsibility, and recognition. Their visibility fades as the system withdraws without explanation. The absence of overt conflict makes the distancing harder to name, which protects the group from having to examine its own behaviour.

By the time the person leaves, whether through resignation or quiet removal, the process has already been normalised. Their absence is no longer felt as a disruption. It is framed as an expected or even necessary outcome. What was lost is not discussed. What remains is a version of events that preserves the group’s sense of stability.

Getting ready to leave

Exit

The target leaves the system and begins the long process of rebuilding.

Exit marks the moment when the scapegoated person is no longer within the system that assigned them the role. The departure may happen because they were pushed out, because they chose to leave, or because they reached a point of physical or emotional exhaustion that made staying impossible. Regardless of how it happens, the act of leaving creates the conditions in which reflection and recovery can begin.

Once they are outside the environment, the person is better able to recognise the pattern they were caught in. They begin to understand the dynamics that shaped their experience, the responses that protected them, and the toll that constant vigilance has taken on their sense of self. The emotional impact that was held at a distance during the period of survival often begins to surface. Grief, anger, and disbelief may appear, not as new feelings, but as ones that could not be processed in real time.

Rebuilding after scapegoating is neither quick nor linear. It requires a re-evaluation of value, identity, and safety. The person begins to question what they once tolerated, what they now need, and how they want to relate to others going forward. Trust is rebuilt carefully and boundaries are shaped more deliberately. There might still be questions that go unanswered, and accountability might never come, but the person is no longer living inside a role that was imposed upon them.

Exit does not offer resolution in the way people often hope it might. It does, however, make room for clarity, agency, and self-definition. It is the point at which the person begins to reclaim their own story. It no longer needs to be explained or defended, but can now be carried and reshaped on their own terms.

Closure

Post post exit reflection

Final thoughts

Scapegoating is often the result of a workplace’s immune system reacting to a perceived threat, where the group moves to eject what it cannot tolerate in order to preserve its internal stability. It is a predictable outcome in environments where dysfunction is maintained, accountability is avoided, and cohesion is valued more than honesty. The person who is scapegoated is rarely targeted because of a single action or flaw. More often, it is because they have, often without realising it, disrupted the unspoken agreements that allow the system to remain intact and emotionally undisturbed.

The Scapegoating Playbook outlines the relational sequence that allows this process to unfold in plain view, often without being named or challenged. Each stage builds on the one before it. Group dynamics begin to shift in ways that distance the target while preserving the group’s preferred version of itself. These shifts happen through exclusion, implication, and silence rather than open conflict or formal decisions.

Recognising this pattern may not reverse what happened, but it offers something just as important. It creates language and structure for making sense of the experience. It allows people to begin separating their identity from the role they were given, and to understand the forces at play without turning that insight against themselves. Seeing the structure clearly is a step toward resisting it, whether you have been the target, the bystander, or the person who stayed silent.

For those who have lived through scapegoating, the aftermath might not include resolution or repair from the system itself. Even without those things, it is possible to move forward with greater clarity, stronger boundaries, and a deeper commitment to relationships and environments that do not depend on someone else’s exclusion in order to function. It is possible to re-engage without disappearing, to lead without overfunctioning, and to belong without having to earn it through silence.

The story changes when you stop performing the part you were given and begin telling the truth of what you saw and experienced.

Many of you have followed my posts on LinkedIn about scapegoating, power, and relational dynamics at work. I’ve been collecting those stories and commentaries into a short book — part memoir, part framework, part field guide. It’s in development now and I’ll share more soon!

Hack narcissism and support my work

I believe that a common threat to our individual and collective thriving is an addiction to power and control. This addiction fuels and is fuelled by greed - the desire to accumulate and control resources in social, information (and attention), economic, ecological, geographical and political systems.

While activists focus on fighting macro issues, I believe that activism also needs to focus on the micro issues - the narcissistic traits that pollute relationships between you and I, and between each other, without contributing to existing injustice. It’s not as exciting as fighting the Big Baddies yet hacking, resisting and overriding our tendencies to control others that also manifest as our macro issues is my full-time job.

I’m dedicated to helping people understand all the ways narcissistic traits infiltrate and taint our interpersonal, professional, organisational and political relationships, and provide strategies for narcissism hackers to fight back and find peace.

Here’s how you can help.

Order my book: The Little Book of Assertiveness: Speak up with confidence

Support my work:

through a Substack subscription

by sharing my work with your loved ones and networks

by citing my work in your presentations and posts

by inviting me to speak, deliver training or consult for your organisation

Fascinating stuff.

I’ve always hated these subtle, covert power games. The victim can never fight back because there’s nothing obvious to fight back against.

Thankfully, I work for myself but, if I were an employer, I’d discipline staff if I even detected this was going on.

Integrity is everything, and plausible deniability be damned.

There definitely is a Playbook, whether it’s at work or in your home. Amazing that it is replicated with a pattern that so many seem to follow. Is there an Amazon bestseller? Narcissistic Playbook for Dummies?